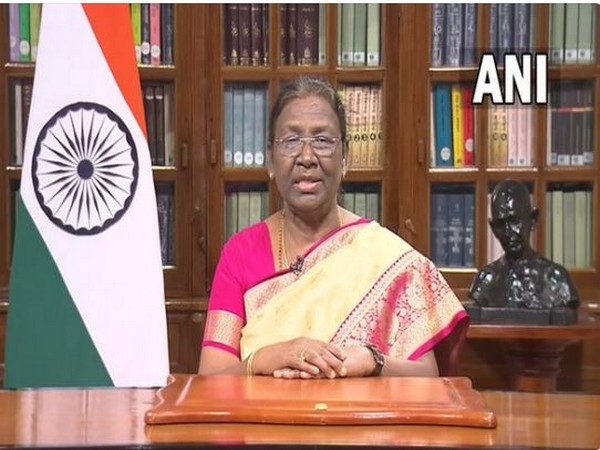

Photo Source: ANIIndian Air Chief becomes first foreign service head to review Bangladesh Air Force passing out paradeNew Delhi [India], June 29, 2021 (ANI): Signifying the strong bonds between India and Bangladesh, Indian Air Force chief RKS Bhadauria reviewed the Passing Out Parade and Commissioning Ceremony at Bangladesh Air Force Academy (BAFA) at Jashore in Bangladesh.This was the first instance when any foreign chief was invited to review the Parade as the Chief Guest, the Indian Air Force said. Bhadauria was invited by his Bangladeshi counterpart Air Marshal Shaikh Abdul Hannan to review the Passing Out Parade and Commissioning Ceremony at Bangladesh Air Force Academy (BAFA).The event was held in Jashore on Monday. The two-day visit was highly significant in view of the Golden Jubilee of the historic victory in 1971 War for Liberation of Bangladesh. While addressing the graduating trainees on parade, CAS complimented them for an excellent parade and noted the rapid progress being made in all aspects of military-level interactions, with bilateral defence cooperation having become an important pillar in the deep historical and fraternal ties between India and Bangladesh.The Indian air chief described this event as a reflection of the excellent state of professional relationship between the two Air Forces based on mutual trust and understanding. He expressed confidence that his presence in BAFA during this historic 50th year of Liberation War would reinforce the already strong and multi-dimensional partnership between the two Nations.During his stay in Bangladesh, the CAS held discussions with his host, the Chief of Air Staff Bangladesh Air Force as well as the Chief of Army Staff and Principal Staff Officer, Armed Forces Division, wherein matters of mutual interest and avenues to further strengthen the all-encompassing defence cooperation were discussed. He also interacted with the High Commissioner of India, Vikram K Doraiswami during his stay in Dhaka. (ANI)

Photo Source: ANIIndian Air Chief becomes first foreign service head to review Bangladesh Air Force passing out paradeNew Delhi [India], June 29, 2021 (ANI): Signifying the strong bonds between India and Bangladesh, Indian Air Force chief RKS Bhadauria reviewed the Passing Out Parade and Commissioning Ceremony at Bangladesh Air Force Academy (BAFA) at Jashore in Bangladesh.This was the first instance when any foreign chief was invited to review the Parade as the Chief Guest, the Indian Air Force said. Bhadauria was invited by his Bangladeshi counterpart Air Marshal Shaikh Abdul Hannan to review the Passing Out Parade and Commissioning Ceremony at Bangladesh Air Force Academy (BAFA).The event was held in Jashore on Monday. The two-day visit was highly significant in view of the Golden Jubilee of the historic victory in 1971 War for Liberation of Bangladesh. While addressing the graduating trainees on parade, CAS complimented them for an excellent parade and noted the rapid progress being made in all aspects of military-level interactions, with bilateral defence cooperation having become an important pillar in the deep historical and fraternal ties between India and Bangladesh.The Indian air chief described this event as a reflection of the excellent state of professional relationship between the two Air Forces based on mutual trust and understanding. He expressed confidence that his presence in BAFA during this historic 50th year of Liberation War would reinforce the already strong and multi-dimensional partnership between the two Nations.During his stay in Bangladesh, the CAS held discussions with his host, the Chief of Air Staff Bangladesh Air Force as well as the Chief of Army Staff and Principal Staff Officer, Armed Forces Division, wherein matters of mutual interest and avenues to further strengthen the all-encompassing defence cooperation were discussed. He also interacted with the High Commissioner of India, Vikram K Doraiswami during his stay in Dhaka. (ANI)

Speaking at the ‘Global scourge of terrorism: assessment of current threats and emerging trends for the new decade’, V S K Kaumudi said, ‘another add-on’ to ‘existing worries’ is the use of drones.

India called on the world to remain united against tendencies of labelling terrorism based on terrorist motivations especially those based on religion, and political ideologies.

The possibility of the use of weaponised drones for terrorist activities against strategic and commercial assets calls for serious attention by the global community, India has told the UN General Assembly, a day after two explosives-laden drones crashed into the Indian Air Force (IAF) station at Jammu airport.

A fresh attempt to attack a military installation with the help of drones was foiled by alert Army sentries at the Ratnuchak-Kaluchak station who fired at the unmanned aerial vehicles that flew away, an incident that came hours after an IAF station saw the first terror attack using quadcopters.

The first drone was spotted at around 11.45 pm on Sunday followed by another at 2.40 am over the military station, which witnessed a terror attack in 2002 in which 31 people were killed, including 10 children. The IAF attack is the first instance of suspected Pakistan-based terrorists deploying drones to strike at the country’s vital installations.

“Today, misuse of information and communication technology such as internet and social media for terrorist propaganda, radicalisation and recruitment of cadre; misuse of new payment methods and crowdfunding platforms for financing of terrorism; and misuse of emerging technologies for terrorist purposes have emerged as the most serious threats of terrorism and will decide the counter-terrorism paradigm going forward,” Special Secretary (Internal Security), Ministry of Home Affairs in the Government of India, VSK Kaumudi said.

Speaking at the ‘Global scourge of terrorism: assessment of current threats and emerging trends for the new decade’, he said, ‘another add-on’ to ‘existing worries’ is the use of drones.

“Being a low-cost option and easily available, utilisation of these aerial/sub-surface platforms for sinister purposes by terrorist groups such as intelligence collection, weapon/explosives delivery and targeted attacks have become an imminent danger and challenge for security agencies worldwide,” he said at the 2nd High Level Conference of the Head of Counter-Terrorism Agencies of the Member States in the General Assembly.

“The possibility of the use of weaponised drones for terrorist purposes against strategic and commercial assets calls for serious attention by the member states. We have witnessed terrorists using UAS to smuggle weapons across borders,” Kaumudi said, according to his statement issued by the Permanent Mission of India to the UN.

Kaumudi said the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent isolation have further accentuated the impact of the internet on people making them vulnerable to radicalisation and recruitment by terrorist groups.

Spreading terrorist propaganda through the use of “indulging video games” is another strategy that was deployed by terrorist groups during the pandemic, he said.

“It is imperative for countries to adopt a multi-pronged approach to tackle the global threats emanating out of misuse of new technologies particularly aiming towards terrorism and violent extremism conducive to terrorism,” he said.

India called on the world to remain united against tendencies of labelling terrorism based on terrorist motivations especially those based on religion, and political ideologies.

“This will certainly divide us and weaken our fight against terrorism,” Kaumudi said.

He said the trans border nature of this threat calls for collective and unified action by the international community, without any excuse or exceptions, ensuring that those countries which provide safe havens to terrorists should be called out and held accountable.

India noted with concern that internet and social media platforms have turned into indispensable resources in the toolkit of global terrorist groups for spreading terrorist propaganda and conspiracy theories aimed at spreading hatred among societies and communities and offer additional radicalisation opportunities which may proliferate globally.

“The increased use of closed group communications adds to the concern,” he said.

Kaumudi told the General Assembly that continuing advancements in evolving technologies, such as Artificial Intelligence, robotics, “deep fakes”, blockchain, dark web are fraught with the risk of being abused by terrorists. “Already, cryptocurrencies, virtual assets, crowdfunding platforms are helping terror financing, owing to anonymity and un-traceability of these technologies,” he said.

India has put in place an elaborate counter-terrorism and security architecture, besides introducing a series of measures in the cyber-space encapsulating counter-radicalisation and de-radicalisation strategies.

An Indian Air Force Sukhoi Su-30MKI jet flies in the backdrop of Himalayan mountain ranges

The lack of “jointness”, integrated planning and synergy between the three armed forces, has been a distinctive feature of the Indian military

by C Uday Bhaskar

India is all set to create four new theatre commands and, in all likelihood, this will be announced by Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi from the Red Fort on August 15. These new commands will be raised and operationalised over a two-year period and will be viable by August 2023.

The new commands will include the integrated maritime theatre command (IMTC) and the integrated air-defence command (IADC), which had been earlier described as a low-hanging fruit in the radical rewiring of India’s higher defence management, a policy initiative that has been in stasis since the 1999 Kargil War. The other two commands will be China- and Pakistan-specific.

PM Modi announced the creation of the Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) in his August 2019 Independence Day address. The first incumbent, General Bipin Rawat, assumed office on January 1, 2020, and this was welcomed as a much-needed but long-delayed first step in the reorganisation of India’s higher defence management (HDM).

The lack of “jointness”, integrated planning and synergy between the three armed forces, has been a distinctive feature of the Indian military. In particular, there here has been less-than-satisfactory utilisation of airpower, perhaps due to a degree of diffidence and lack of clarity in the use of trans-border military capability embedded in Indian strategic culture. India did not use its modest-but-credible airpower in October 1962 when China chose to teach Jawaharlal Nehru a lesson in realpolitik.

And for the record, there was no reference to airpower in Galwan of 2020. Similarly, the 1999 Kargil War and the 1987 Indian Peace Keeping Force operation in Sri Lanka saw less than optimal integration of airpower in the military effort.

Thus the need for more effective jointness/synergy among India’s three armed forces was acknowledged post-Kargil and the report of the Group of Ministers (2000) recommended the creation of the post of a CDS and a VCDS as the “first major step in establishing synergy and ‘jointness’ among the Armed Forces”. Very soon, the first integrated, tri-service command was established in Port Blair as the Andaman and Nicobar Command (ANC), with then Vice-Admiral Arun Prakash as the first Commander-in-Chief. It was expected that, progressively, greater jointness/synergy would be nurtured and that India would move towards setting up such tri-service commands, wherein the sum of their individual assets under a single commander would be more effective than that of their individual verticals that were disparately located.

However the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government, at the time, was unable to pursue these initiatives with the requisite resolve and this went into the back-burner for over a decade. To his credit, PM Modi, after an indifferent scorecard in his first term in the domain of defence management, accorded this high priority in his second term, and hit the ground running.

In August 2019, CDS was announced. In August, the new commands are on the anvil and the directive is that these commands should become operational in August 2023. This taut timeline and the visible political direction is commendable, but this long-delayed reform towards enabling greater jointness in India’s HDM will call for making haste slowly, and only after objective deliberation among the principal stakeholders.

Recent media reports refer to a degree of dissonance within the military and the Indian Air Force has been painted as the dog-in-the-manger in the creation of the new commands. This is unfortunate and undesirable, whatever be the truth behind such aspersions.

India’s integrated tri-service commands (one is hesitant to use the word theatre) can become truly effective only when all the interlocutors are brought onto the same page consensually and by persuasion. The reforms in HDM and related military command structure cannot be effectively realised by political diktat. Compliance can be ensured, albeit in a sullen manner, for, in a democracy, the political direction must be obeyed by the military but giving all the three forces a robust sense of ownership would lay stronger foundations.

Thirty years after economic reforms, there are lessons for India as it embarks on the next phase of reforms in the defence domain. A combination of political leadership, technocratic talent, and willingness to build on work left behind by previous governments helped steer through the reforms. PM Modi has given the necessary direction and priority to reforming India’s defence management. Defence minister Rajnath Singh has an onerous responsibility and, given his political experience both as former party president and home minister, he would be able to provide the necessary political leadership and heft. But the rigorous staff work and internal deliberations within the government will have to be undertaken objectively and without any rancour and in a non-partisan manner. Effective and enhanced jointness to prevent another Galwan/Pulwama must be the objective.

The use of rogue drones by terrorists, smugglers or hostile nations have been, for the past few years, been cited as a serious concern, but the capability to counter this threat is still in a nascent stage in India.

The twin blasts inside the Air Force Station, Jammu, on Sunday that were suspected to have been caused by drones and an Army sentry reportedly shooting at a drone flying near the Kaluchak Military Station today have brought into focus the security risks posed by unmanned aerial vehicles.

The use of rogue drones by terrorists, smugglers or hostile nations have been, for the past few years, been cited as a serious concern, but the capability to counter this threat is still in a nascent stage in India.

The armed forces as well as police are developing anti-drone capability that includes a doctrinal approach to counter the threat as well as the technology and physical systems to detect and neutralise drones. There are several means by which a drone can be detected, identified, disabled or destroyed, which includes radar, infrared, laser, opto-electronics, electromagnetic and acoustic means along with the use of guns, rockets or missiles. These can be fixed, vehicle mounted or man-portable.

Last year, the Defence Research and Development Organisation had unveiled an anti-drone system designed by it, which is reported to have been deployed selectively so far, with state-owned Bharat Electronics Limited designated as the production agency.

The Army’s Directorate of Air Defence is undertaking a project to develop counter measures against unauthorised flying objects that can be used for surveillance or attack. Launched over a year ago, the Army expects the feasibility study to take around two years, with other two or three years for developing a technology solution.

The BSF is also in the process of acquiring anti-drone systems. Its requirement is for a ground-based standalone platform capable of detecting a lone suspicious flying object or a group of UAVs and react within 10 seconds.

Being border states and given their history of terrorism, Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir are vulnerable to cross-border smuggling and terror attacks. Security forces have reported an increase in drone activity in border areas, with several instances of drones violating the Indian air space of being used to drop arms and ammunition on this side of the border.

Difficult To Track

Most drones used for cross-border smuggling of arms and ammo or for attacks are much smaller than conventional aircraft. Since low altitude and their minuscule radar makes them difficult to track electronically, ground forces have to rely on visual sightings and audio signals

No Funds For Tech

The Punjab Police are facing financial issues in the procurement of anti-drone technology. Sources say several meetings have taken place at the highest level and some private companies have also made presentations, but due to high cost it is yet to be approved.

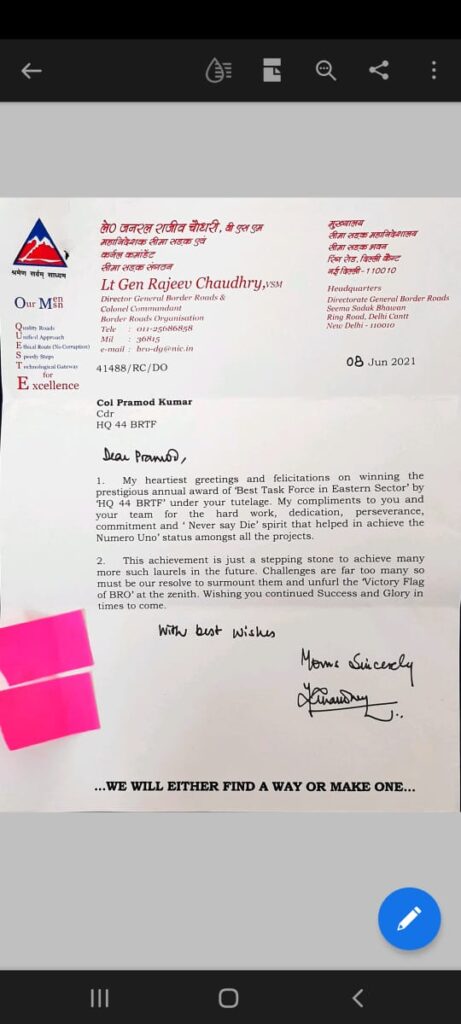

Recalling the chance meeting of Col Krishan Lal Wahi with the legendary Pak athlete, his request for medical aid for a fellow soldier and how the Col’s son offered to donate blood

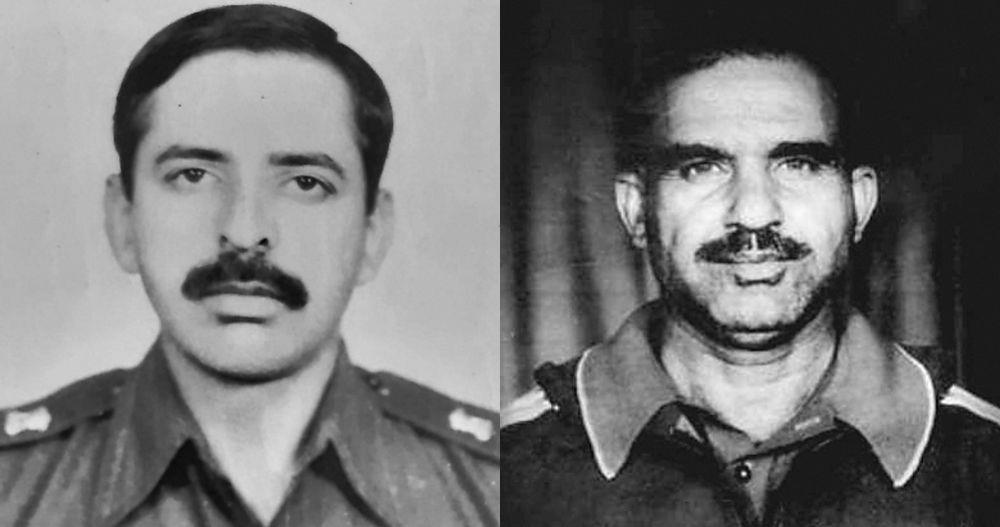

(L-R) Lt Col Ajay Wahi, Subedar Abdul Khaliq

Lt Col AK Ahlawat

It was December 20, 1971, and the war had ended a few days ago. Ajay was a pre-medical student in DAV College, Chandigarh. He reached the Chandigarh bus stand to catch the first bus to Jammu. The morning was cool and winter’s haze hung on the roofs of the lined-up buses. A few minutes before 7, the Sikh driver in khaki climbed behind the wheel. By evening, Ajay was with his father, Col Krishan Lal Wahi, posted at Udhampur where the Army’s 15 Corps was headquartered. The family was grieving. On December 6, they had lost Flight Lieutenant Vijay Kumar Wahi in aerial battles over Chhamb-Akhnoor. He was flying a Sukhoi 7 with the IAF’s 101 Fighter Squadron. The mood of the family was sombre and quiet. Vijay Wahi was the hero brother, the fighter pilot brother whom Ajay hero-worshipped.

Then one day his father said, “Ajay, I have to visit the Prisoner of War camp here in Udhampur. Would you like to come along?”

So they drove in an Army Jonga, turned left from the nullah before the Base Hospital and reached the barbed wire cage of the PoW camp. The elderly time-scale Sikh Colonel who was the camp commandant took them to his hut and gave them tea and biscuits.

“Anyone from Khooshab Sargodha area in the camp?” asked Colonel Wahi.

‘I think there might be a few,” he said, pressing the office bell. An orderly appeared.

“Go call the Pakistani senior JCO.”

A man in khaki came in, saluted and disclosed his name, number, rank and unit.

“How did you get caught as PoW, JCOs are at gun position in the rear?” asked Col Wahi.

“Janab, there is a lot of difference in our armies. In the Indian Army, officers do Artillery Observation Post duty. In our army, officers remain behind at gun positions and JCOs are at Forward Observation Posts to direct artillery fire. My observation post got over-run by the Indian infantry and I was taken prisoner.”

Colonel Wahi was silent for a few moments trying to recollect something. “Isn’t there a Pakistani athlete of your name who had competed against Milkha Singh in races?” he asked.

The Pakistani came to stiff attention and said, “Janab, I am the same man.”

Subedar Abdul Khaliq of 8 Medium Regiment was an ace sprinter whom Pandit Nehru had called the “The Flying Bird of Asia”. When Milkha Singh won against him, Pakistan President Gen Ayub Khan called the legendary athlete, who passed away recently, the “Flying Sikh”.

Colonel Wahi and Subedar Khaliq exchanged notes about their native province for some time and then the JCO asked, “Gustakhi mauf howey tan janab ek arz karan (Sir, if you permit, I have an appeal).”

“Bilkul dasso (sure, go ahead).”

“Janab eik munda hai, ohh nu bayonet lagya hai. Doctor saab roz aande ne, oh nuu dekhdey ney, parr ohh thik nahi ho rayaa (Sir, there is a soldier of ours who has a bayonet wound, the doctor comes every day to attend to him but his condition is not improving).”

“Badaa tezz bukhaar hai mundey nuu aur saadey paasey daa he hai (The lad has high fever and he is from our province itself).”

He asked if a surgeon could have a look at him as he was slipping away fast and maybe his life could be saved.

The senior surgery adviser at the Base Hospital was a white-bearded Sikh who also came from Khooshab. He was Colonel Wahi’s tennis partner. They gave him a call and related the case. The surgeon, Colonel Baldev Singh, asked for the PoW to be sent to the Base Hospital and sent an ambulance.

In the evening, the surgeon met Col Wahi at the tennis court. The young schoolboy also accompanied his father.

“Thank God you sent him just in time. The bayonet has gone deep inside and he has peritonisis. Very serious infection has developed inside and he will have to be operated upon. We need some blood for him. I have told the staff that I will operate after I play tennis and in the meantime they are to look for some donor of the same blood group.”

Ajay Wahi, who was overhearing the conversation, asked, “Sir, what blood group is he?”

“He is B Positive.”

“I am also B Positive.”

The surgeon looked at Ajay, “You will donate blood for this Pakistani soldier?”

“Yes I will.”

“Are you sure?”

“Of course I will.”

“Come son, then let’s go to the hospital.”

They reached the hospital and the senior surgeon said, “Here is the voluntary donor, I will just change and operate.”

Then the father and son came back. The father said, “Son, I thought that you were still a kid, but I have realised today that my son is no longer a boy, he is a man.” Lt Col Ajay Wahi, a pathologist, had donated blood 130 times till he reached the age of 65.

Our energies need to be devoted to beefing up our single-service inventories and effecting cadre reviews to achieve desirable teeth. Bringing in another level of operational command in the guise of a theatre commander is inapt for our strategic security posture and an exercise in futility. The attendant handicaps would be inadequate domain expertise of a different service theatre commander and undesirable parcelling out of air power assets.

Unsuitable: Creating theatre commands is putting the cart before the horse. PTI

The Kargil Review Committee recommended a ‘first among equals’ Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) — albeit a four-star one approved by the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) in December 2019 and not a five-star one, as was desirable in a nuclearised scenario and was expected to enhance the procurement and operational integration of the three services.

But a series of missteps such as pension reforms and theaterisation bode ill for national security. The attempt by the DMA to create ‘theatre commands’ unabashedly promotes turf battles between the three services rather than leading to defence capability integration. The need for India to replace its existing seven each of Army/ IAF and three Naval single-service sectoral commands with five or so integrated theatre commands — west, north and east for Pakistan/China threats, air defence and maritime theatres — is being proposed without thinking it through.

China and Pakistan-centric operations would demand the involvement of multiple proposed theatre commands such as the Western, Northern and Eastern Land Theatres as also the Maritime and Air Defence Theatres. The need is to clearly recognise the traditional war-waging mindset and domain orientation of the Army, Navy and Indian Air Force.

The Army generally has a battle horizon of “a day’s march”, within which it sees its battle space. General Sundarji attempted to widen this to around 100 km, with his laudable mechanised ambitions.

The Navy, on the other hand, operates in a few knots per hour domain, with even gunboat diplomacy and carrier battle groups taking several days to be manifestly effective.

The Air Force is the truly strategic service, capability and mindset wise. A fighter bomber on a tactical mission is capable of achieving strategic goals, as exemplified by the timely IAF Hunter and MIG-21 aircraft strike on the East Pakistan Government House on December 14, 1971, instrumental in the capitulation of the entire Pakistani Eastern Army.

All three services have their priorities for war-fighting, derived from national security objectives and associated service doctrines. The IAF was the first to articulate an Air Power Doctrine in the early 1990s. The Navy followed up with its own doctrine and finally the Army, too.

An attempt to articulate a joint doctrine is now gaining traction, more so after the formation of the Integrated Andaman & Nicobar Command. Be that as it may, joint war-fighting procedures and norms have evolved over the years, functioning rather well indeed at the service command, i.e. operational levels.

The same has been amply demonstrated in the wars so far waged by the Indian defence forces, including in Kargil and the latest Ladakh standoff. There is no need now to try and fix a system that is not broken.

Every nation needs to adopt military organisations which suit its national ethos and threat dynamics. We do not have a five-star joint chief of staff and talking of creating theatre commands at this juncture is putting the cart before the horse.

Our energies now need to be devoted towards beefing up our single-service inventories and effecting suitable cadre reviews to achieve desirable teeth: to tail ratios. Whereas, bringing in another level of operational command in the guise of a theatre commander is inapt for our strategic security posture and bound to be an exercise in futility. The serious attendant handicaps would be inadequate domain expertise of a different service theatre commander and undesirable parcelling out of expensive air power assets.

Valuable soft skills and other command and control tools such as AWACS, AEW, flight refuelling aircraft, strategic transport/ airlift capability, electronic combat assets and other force multipliers are meant to be dynamically switched from one combat zone to another, depending on the situation. They are definitely not to be brought ‘under the command’ of one expert military leader. A novice air commander orchestrating air power in war is fraught with danger. Aping the organisational structures in the US, Israel or China (or even the puny Maldives, as protagonists have sought to) would be detrimental to operational efficiency, especially of a nation’s air force.

The prevalent career profiles in the three services do not cater to ‘maroon’ tenures in the upward hierarchical transition of a service officer. India is not yet ready to experiment with ideas such as theaterisation.

The other important deterrent against theaterisation is the dwindling force structure of the IAF, already down to 30 squadrons (and slated to reduce further), thanks to slow accretions. The dangers of parcelling out of air assets, as theaterisation envisages, need not be emphasised.

Further, the concept of a land or maritime-centric theatre is anathema to true integrated war-fighting, which is what we should strive for: a unified thinking amongst the practitioners, rather than cosmetic organisational tinkering.

If the intent is only to have a single operational commander overall, we should be aiming for a single theatre, which is what the Indian armed forces have been oriented to all these years.

Thus, the theatrisation proposal is ridden with operational lacunae which are now being sought to be thrust on an uncooperative IAF, whereas any sensible reorganisation should encompass technical weapon upgrade and efforts to better the teeth-tail ratios of our combat arms.

In December 2019, heavy-lifting drones were used by Pakistan to drop AK-47 rifles, counterfeit currency and narcotics in Punjab’s border districts. But the Jammu drone attack is something new. Contemporary drones cost little, and availability is aplenty. Drones represent an asymmetric threat that can cause serious damage and create panic.

Wise Course: It is better to bring down a drone intact for forensic analysis and intelligence-gathering than destroy it. Reuters

In the age of the Almighty Computer, drones are the perfect warriors. They kill without remorse, obey without kidding around, and they never reveal the names of their masters.

Eduardo Galeano, Uruguayan writer

IN August 2017, aircraft carrier Queen Elizabeth of the UK Royal Navy was docked at Invergordon when an amateur photographer flew a drone close to the giant battleship. When the drone sensed a high wind risk, it landed itself on the ship. The pilot (with the remote) told BBC that he could easily have carried two kilograms of high explosives and left it on the deck.

An assassination attempt was made on Venezuela President Nicolas Maduro on August 4, 2018, with a drone. Two drones loaded with one kilogram of explosives each were flown close to the president while he was addressing a military parade. They were detected by the alert security personnel. One drone was electronically diverted from its course and the second crashed against a wall.

December 20, 2018, saw drones dramatically disrupt air travel after someone brought London’s Gatwick airport to a complete halt by flying drones intermittently over the airport’s lone runway. Air traffic at other London airports, including Heathrow, was also disrupted momentarily over fears of a coordinated drone assault against all five of London’s commercial airports.

In December 2019, heavy-lifting drones were used by Pakistan to drop AK-47 rifles, counterfeit currency and narcotics in 10 sorties spanned over eight days in Punjab’s border districts More such incidents have been reported. Sunday’s drone attack on the Jammu Air Force base is new and extremely belligerent. This aggressiveness needs to be nipped in the bud to prevent further escalation. Clearly, the threat from the drones is a cause for serious concern. Contemporary drones cost little, and availability is aplenty. Drones today represent an asymmetric threat that can cause serious damage and create panic.

Drones being small, silent and discreet are difficult to detect and bring down. They can be pre-programmed and/or remote controlled even with smart phones. Rapid miniaturisation of electronics and batteries are a boon to the growth of drones. Additional features like auto landing, dynamic homing and orientation control provide greater stability and effective control. High-end cameras with axis stabilisation provide a smooth and stable recording experience with high-quality videos. They are symmetric in shape and can fly in any direction. They can be armed with weapons, explosives and/or cameras. They can also carry hacking-capable devices, such as small on-board computers (e.g., a Raspberry Pi), Wi-Fi/Bluetooth dongles (to monitor and detect vulnerabilities in networks) and trigger an attack on the computer/network.

Big investments in countermeasures are inescapable. Any control measure would necessarily be working under extreme capability of precision and real-time response. To observe, detect and analyse a rogue drone would require tracking its flight path precisely. An effective sensor system will monitor electronic radio data and the designated airspace with video cameras (quite like the CCTVs watching over a crowded marketplace). These devices would trigger alarms automatically on spotting and initiate the analysis process, identify control commands being transmitted to the drones by radio and register the drone type and characteristics to classify the threat.

Once a hostile drone is identified, measures to bring it down commence. These may be the use of guns and explosives to destroy it or electronically jam it and force it to land. It is very desirable that the actions of detection, identification and destruction/disablement take place automatically. This would require all the participating defensive elements to be electronically integrated. The electronics used must not pose a threat to other friendly flying objects in the vicinity and cause collateral damage to infrastructure. The countermeasures will also have to be layered and gridded to provide an effective defence shield; any single point of failure is simply unacceptable.

It is preferable that instead of destruction, the drone is brought down intact to allow forensic analysis and intelligence-gathering to eliminate threats and prevent future attacks. Some well-established physical countermeasure are: well-trained snipers to shoot them down with pellet guns, man-portable launchers to launch nets to physically capture drones and bring them down with a parachute. Electronic countermeasures take over remote control signals and the Global Positioning System (GPS) signals to disorient and capture the drone. Lasers are becoming a feasible option. However, directed energy weapons are still experimental from an operational standpoint.

The detection and identification systems include contemporary technology devices like modular and fully configurable 3D radar sensor, MIMO (multiple-input multiple-output) radars to improve detection accuracy, radio frequency sensors and acoustic sensors. The electronic countermeasures include a fully integrated and automated directional or omnidirectional jammer for neutralisation of drones and a dedicated web application for controlling the system.

As the concern surrounding drone safety continues to grow, fresh and innovative technologies will continue to evolve, and the trick lies in keeping pace. The time to prevent any future belligerence is now.

Military sources say such attempts have been intercepted in recent times in the Jammu sector. It points to high confidence, and an intent to raise alarm, possibly to push the Air Force into retaliation in terms of deliberate flights close to the India-Pakistan border. That could raise bilateral temperatures very quickly.

Scare In The Air: There has been a spate of drone activity along the border, but we need to separate military drones from improvised vehicles. PTI

IN what can be classified as an escalation in violence, drones were used to cause at least two explosions in the technical area of Jammu airport, which is being used by the Air Force. Though it caused only minor injuries to two personnel, the incident could have been much worse. The drone could have hit a parked aircraft, resulting in a terror attack of no small proportion. This is a quantum jump in terrorist capability in India. No doubt about that at all. That said, it is not the drone itself that is the sole issue, but the intent and intelligence in how it is used.

Commercial drones relatively available in India, like the DJI Phantom 4, with an added payload of explosives of up to a kilogram or more, would have an operational range of about a kilometre. Since the explosion was at night, the onboard camera was probably not of much use for targeting, explaining why it missed any worthwhile target.

Even if coordinates were fed in, it is important to understand that commercial drones are simply not geared up for this kind of precision task. Showering flowers on a visiting VIP, yes; targeting a specific aircraft, no. If it was a commercial drone, then the operator was close to the airport, probably on the roof of a building, guiding the drone. Reports, however, seem to indicate that the drone flew across the border and back, a total of some 40 km, indicating a far more technology-intensive and probably larger machine, that raises a different set of possibilities.

The Jammu airport is just about 14 km from the Pakistan border, which makes it vulnerable to such attacks. Islamabad has a vigorous (UAV unmanned aerial vehicle) programme that includes long-range ones of upwards of 1,000 km and tactical drones with a range of some 80 km. The ‘Bravo +’, for instance, has a wingspan of about 14 feet and a payload of some 145 kg. But it defies logic as to why Pakistan’s military would launch such a strike which could squarely implicate it, if shot down. By now, Islamabad knows full well that this is not a government that would hesitate to retaliate. Being Pakistan, there is always the possibility that a part of the armed forces don’t want even the beginnings of a rapprochement with India, that is reportedly on the cards, given sustained backdoor negotiations and apparent overtures by the Chief of Army Staff General Bajwa. But again, a Pak military drone would hardly miss a stationary target.

The more likely possibility is apparent in reports of a spate of drone activity along the border. In October last year, a Chinese surveillance quadcopter was shot down by Indian troops in Kupwara, probably used by smugglers. In June, a rather strange-looking quadcopter was shot down, carrying an assault rifle and grenades. That’s quite a payload. Military sources say diverse such attempts have been intercepted in recent times in the Jammu sector. Available data seems to indicate that all these intrusions were by relatively small machines, that fall under a commercial type of drone, but improvised for its role. A day after the Jammu blasts, alert troops fired at drones over the Kaluchak military station, however, to little effect. The machines seem to have disappeared thereafter. There are no inputs of what these were, and what they were supposed to do. But it points to high confidence, and an intent to raise alarm, possibly to push the Air Force into retaliation in terms of deliberate flights close to the India- Pakistan border. That could raise bilateral temperatures very quickly.

For terrorists, a small drone is a perfect weapon. Barbed wire, armed guards or even a radar can’t spot a weapon that has such a small cross-section, particularly in low altitudes where it can disappear in background ‘noise’. Drones have long been used by terrorists, delivering more psychological effect than actual damage. Hezbollah used drones supplied by Iran to target Syrian rebel strongholds in 2013. The Islamic State has a DIY capability that it has used to gain a strategic advantage, though not much of a battlefield weapon. What it did get was good intelligence and surveillance capability. Then there have been assassination attempts using commercial drones, such as the one against President Maduro of Venezuela in which seven soldiers were injured. The most spectacular use of drones was by Houthis against Saudi Arabia’s oil facilities, which resulted in upending world supplies as its production halted. But those were UAV-X military drones with long range and used ‘kamikaze style’ with warheads of some 18 kg of explosives, according to a UN report. With about 10 of these used, that was not terrorism, it was war. Few remember that Houthis also used Qasef-1 drones to little effect, even though these carry a large warhead. Small drones deliver more in terms of a spectacle, but cause little actual damage. True, in Jammu, one hit against a parked aircraft would have been damage enough. But the key here is not the vehicle. It’s the explosives expert. Find the explosive, and you’ll find the culprit.

It is important, therefore, to separate the clearly military drones from the improvised vehicles used so far, in generating a response. One requires better border policing, the other a huge change in military doctrines. What is clear is that we need to up the alert, but guard against the usual knee-jerk reactions to swoop down on the commercial use of drones that have wide applications at a time of economic stress. There are already attempts to stifle the use of drones through the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) that will effectively prevent legitimate commercial activity. The DGCA’s present ‘Blue Sky’ parameters for instance, may be replaced with stringent KYC procedure, similar to banking systems for an effective oversight. Terror groups like the Lashkar-e-Toiba aim to create panic in an already paranoid bureaucracy, and thereby earn more publicity that increases their stature. It’s a fine line to walk. React with firmness against the real culprit who provides them with shelter and sustenance, but also show that the State is more than capable of protecting its own.

High-tech interception, strict regulation a must

PTI file photo

The drone attack on Jammu’s IAF station on Sunday caught India’s security establishment off guard. This shouldn’t have been the case, considering that unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have emerged as a potent threat in recent years in the country and across the world. The use of drones by cross-border operators to drop arms and drugs in Punjab and Jammu & Kashmir is not uncommon. Terrorists have now taken things to the next level by dropping bombs through UAVs on one of India’s strategic installations. The timing of the attack — days after the PM’s meeting with J&K leaders — is also significant. Though there was no loss of life, the perpetrators’ message was loud and clear: it won’t be a one-off strike and the subsequent ones could be far worse in terms of the damage inflicted. Barely a day after the Jammu incident, Army troops spotted two drones hovering over the Ratnuchak-Kaluchak military area; they opened fire to force both of them to fly away.

The menace of drones had prompted the Directorate General of Civil Aviation to come up with a set of requirements for these UAVs in 2018. Earlier this year, the Union Ministry of Civil Aviation notified the Unmanned Aircraft System Rules, imposing strict compliance norms — right from the R&D stage. This regulatory mechanism, which demands rigorous implementation, must be backed by state-of-the-art anti-drone systems that can intercept and neutralise suspicious remote-controlled aerial platforms. Reliance on the alertness of soldiers to spot drones has its limitations. Technology has a big role to play to keep disruptive elements at bay. India can learn a lot from how other nations are dealing with the airborne intruders.

Drones have become a key component of modern warfare. Iran-backed militia are using UAVs to target US personnel and facilities in Iraq. Several cities of Saudi Arabia are facing drone attacks carried out by Yemen’s Houthi militia. Late last year, drones had helped Azerbaijan defeat Armenia in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. India needs to shed its traditionally reactive approach and opt for pre-emptive action. The challenge is to be well-equipped to prevent terrorists from spreading their wings.