A general recounts the tale of how as a young captain, he and five soldiers manned a post on a peak 20,000 feet above sea level for six gruelling months.

It was early 1986 and almost two years after the Indian Army, supported by the IAF and Army Aviation’s fleet of Mi-8s and Cheetahs, had established dominance over many heights on the Saltoro Range. In a daring but completely unsustainable operation, the Ladakh Scouts of the Indian Army attempted to establish posts over 6100 metres on the lower slopes of the Saltoro Kangri Mastiff that was part of what the Indian army calls the Northern Glacier.

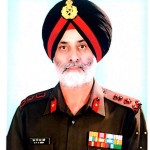

As a young captain and paratrooper, Navkiran Singh Ghei, was posted to the Ladakh Scouts after a stint as an instructor at the National Defence Academy. Ghei went on to command the Indian Army’s only Para Brigade, a division in the northeast in counter-insurgency operations and a corps in Punjab, before signing off his illustrious career as a Lieutenant General, after a three-year stint as the Commandant of the National Defence College, India’s premier institution of strategic learning.

A reticent and ‘feet on the ground’ kind of a general, I was fortunate to get him talking one day on his experience of opening and maintaining a small post at 6135 m (20,250 feet) for over six months with hardly any back-up or logistics support, along with five ‘Nunnus’, as the Ladakh Scouts soldiers were affectionately called.

Having gradually occupied the heights at Bilafondla, Sia la and tasted some success in the Southern and Central Glacier, operational ideas about how to dominate the entire glacier flowed fast and thick from both Northern Command and Army HQs. The importance of establishing more posts in the Northern Glacier was important for the visibility it offered over the entire communication lines that extended towards the Pakistani posts in the Central Glacier and on the Saltoro and Baltoro ridges, particularly from the point of view of providing direction for artillery fire. Consequently, a height was identified that overlooked the Indian posts of Ashok and U Cut (so named because the post itself was located on a ridge that resembled a U Cut) and offered visibility over the Pakistani logistics line that ran up the Bilafond Glacier to support posts like Qaid Post.

As the Siachen imbroglio deepened, the value of the Ladakh Scouts was immense and officers from various regiments were posted there to garner expertise in high altitude operations. At the time, the Ladakh Scouts had its headquarters in Leh, and was divided into two forces of approximately 8-10 companies each. These were known as the Karakoram and Indus Forces after the areas given to them to patrol and operate in.

After a period of acclimatisation at Base Camp and a Forward Logistics Camp, Ghei and his platoon, which included Subedar Sonam as platoon commander, and four hardy Ladakhi troops set out on an arduous climb from 15,000 feet to 20,000 feet, reaching their intended summit at around 8 pm on 26 February 1986. Having pitched their three-man Arctic Tents, they burrowed-in for the night, little realising that they would suffer white out conditions in appalling weather for the next three days.

Ghei recalls that they could not see beyond a couple of feet and had to make do ‘without a pee or a crap for days’. It was a surreal experience for the six men as they huddled in their small tents thinking of how they would survive a week, leave alone for a couple of months as they were tasked to accomplish. Realising that they had bitten off more than they could chew, Ghei radioed for assistance. He sought a larger tent, some supplies and reinforcements.

As the weather cleared, the team established camp for the long haul. It was envisaged that the teams would be rotated every few weeks, but when Ghei’s replacement came a few weeks later, he was all but gone. He barely reached the camp suffering from acute mountain sickness, and had to be evacuated down to the base camp and onwards to the military hospital before he sank further. This meant that Ghei remained on station.

On a clear day, the team had a vantage view of Pakistani supply lines along the Bilafond La glacier and directed artillery shoots on these lines. The rarefied atmosphere posed great challenges for Indian gunners as the lower density meant that the shells encountered lower drag and thus overshot the target by miles as there were no charts for those altitudes. ‘Drop 300m, drop 500m’ were common radio calls that Ghei made to the artillery gun posts to aim much shorter.

They invariably transmitted back to him that the firing picture they were getting pointed at an impact point that was in friendly territory; sometimes even coinciding with his own location. It was a period of uncertainty and virgin territory for India’s gunners, and it was only gradually that ballistics were worked out to ensure acceptable levels of accuracy. One month turned to two, and then almost six. Ghei and his team survived on the post like zombies.

When I asked him how they survived, he said that the Ladakhis were amazing survivors and seeing them gave him the courage to lead from the front. Deprived of sleep, suffering from periodic hallucinations, surviving on milk powder and an odd paratha that the ‘Nunnus’ made him, Ghei lost 10 kg and suffered partial memory loss by the end of his extended six-month vigil on Pt 6135.

When they went down and reported the conditions, the post was abandoned and never manned again. This is a story like the stuff one only reads in the memoirs of mountaineers and their struggle against the odds of nature. The only difference is that it is only one of many that come out of Siachen.

Arjun Subramaniam is a retired Air Vice Marshal from the IAF and currently a Visiting Fellow at Oxford.

Arjun Subramaniam is a retired Air Vice Marshal from the IAF and currently a Visiting Fellow at Oxford.

Arjun Subramaniam is a retired Air Vice Marshal from the IAF and currently a Visiting Fellow at Oxford.

Arjun Subramaniam is a retired Air Vice Marshal from the IAF and currently a Visiting Fellow at Oxford.