Official war histories of our country have remained under sealed covers and archival material is largely unavailable to military professionals, scholars and academics. This has led to an inevitable void in information

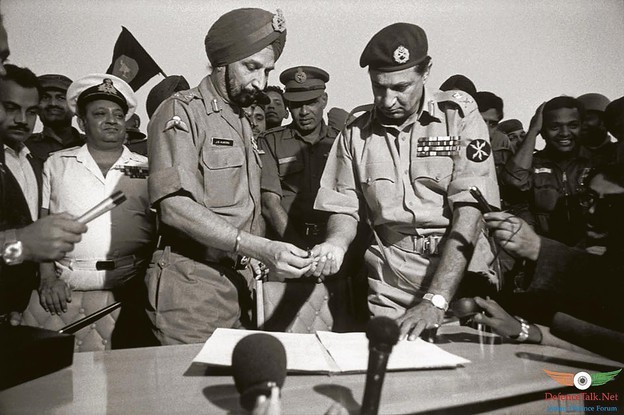

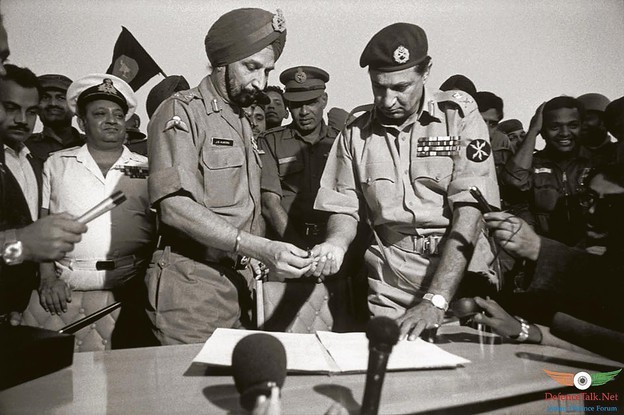

Holding it close to chest: The government’s reluctance to part with official histories of its wars has added to the apathy and loss of objectivity in second-hand accounts

Sandeep Dikshit

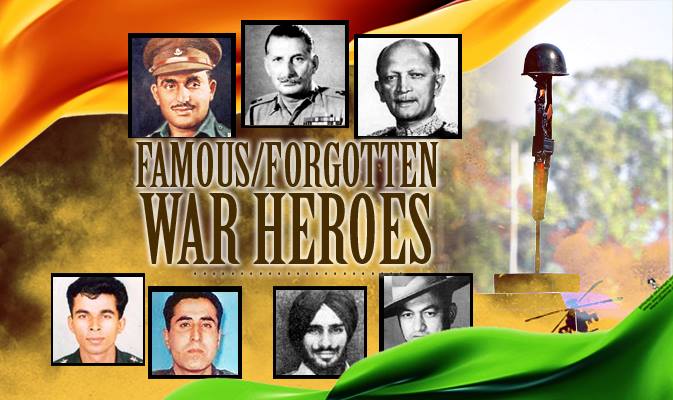

Civilisations indifferent to the recording of history also tend to consign military history to the backseat. Of the four million recorded documents in Indian languages — from the classical era to the 19th century — half are believed to have been irretrievably lost or destroyed and a vast majority of the ones that survive remain untranslated and undigitised.Military history as the basic discipline for the development of national security strategy has remained an underdeveloped genre. But for a clutch of former military men and some academics, the recording of military history is largely hagiography. This approach has suited power centres in India as well as globally because the shortfall in objectivity and honesty helps talk up their exploits while brushing under the carpet instances of ineptness and miscalculations.The Indian government’s reluctance to part with official histories of its wars adds to the apathy and the loss of objectivity in second-hand accounts based on first hand experiences. India did publish the official history of the 1947-48 operations in Jammu and Kashmir and the liberation of Goa in 1961. But the war with China led to a downturn in enthusiasm in the bureaucracy and political class to make public official histories of the subsequent wars. The 1965 India-Pakistan War history was labelled non-official and the 1971 War history remains under sealed covers. The Kargil Review Committee report and a subsequent report by a Group of Ministers, understandably redacted in parts, did provide an official window to the progression of events and the war itself.The erudite man he was, Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao did initiate a move towards openness and making available archival material to military professionals, scholars and academics but the resistance was inevitable. The rules governing the Public Record Act of 1993 took four years to materialise. The Act had promised declassification material at the end of a 30-year cycle. The inefficacy of the legislation led to a fresh debate on the need for openness. While the RTI Act did bring relief to pensioners, the disabled and war widows, it did not result in opening of the archival material. The lacunae led to the setting up of a committee in 2009 comprising bureaucrats and academics with lopsided composition — two historians, seven serving and two retired officials. The committee met a few times in earnest. But last heard, the panel had been wound up and the few suggestions that came its way remained unacknowledged and unimplemented. Given this approach, a knowledge gap is inevitable; not just in stand-alone devotion to the subject but also when benchmarked against international trends.To begin from the beginning, that is the cradle of knowledge, scholars have repeatedly pointed out that the Indian university system is apathetic to the study of military history. Most major and prestigious Central universities offer no course in military history. Even the Departments of Defence and Security Studies (DSS) that exist in about a dozen universities make do with an optional paper and are reported to be bereft of a professional faculty.Although some limited work exists of the pre-Independence British period, there is no serious original work by an Indian author on modern war studies. Rather, mostly foreign scholars excel here and are widely quoted.

A former Defence Secretary recalls“Coming back to the Defence Secretary’s office, the complex, if it may be called, consists of a room for his staff officer, a separate conference hall and a spacious, well-laid out space in the Defence Secretary’s office to hold meetings. On the left side of the office of the Defence Secretary are wooden shelves, stacked with files and books. One of the most coveted books is the Henderson Brooks Report, which is kept under lock and key. It cannot be taken out of the Defence Secretary’s room and cannot be given or lent to any person, including the ministers. I must confess that I have not seen the relevant Order but these instructions are orally passed on from one Defence Secretary to another….

Lessons from others

Both in the US and Australia, it took almost 30 years to integrate the three services. Ultimately, it had to be done by legislation. In India, we are ensuring this coordination and looseness by government orders. Eventually, a law would be required to legally enforce closeness and coordination. Excerpted from Born to Serve: Power Games in Bureaucracy by Yogendra Narain. Manas

Disaffection in forces

Little things can trigger disaffection. The British officers of the East India Company’s army made light of the unease among Indian soldiers over the use of grease on their bullets. The insignificance attached by them to this issue and their subsequent apathy to addressing the misgivings among its infantry gradually snowballed into the First War of Independence. Similarly, because of the absence of source material, sociologists and historians have not been able to expound on the few instances of protest after Operation Bluestar. If at all, the reports might be held by disparate institutions: the military, of course, but also the Intelligence Bureau and the intelligence and police apparatus of states where the incidents occurred. The lessons from the disaffection, however, cannot be applied to the current unease over salaries, order of precedence and pensions.

Northeast, always forgotten

The Northeast has often been a theatre of war in the past. In the 1962 War, it figures in popular lore just once and that too as supporting civilians: Rifleman Jaswant Singh Negi of 4th Garhwal Rifles was assisted by two local girls in keeping off the Chinese. Otherwise, it is rare to come across any book, paper or article about the involvement of Northeast soldiers on either side of Independence. The fact is many young men joined the military to fight the Japanese to defend their home turfs of Kohima and Imphal as well as further afield in Burma and Malaya. Several, for whom age had rendered them unfit for enrolment as soldiers, scouted for intelligence at great peril.In addition, the region has been neglected in the recording of oral history that would have set some of the myths about the 1962 War at rest, especially the one that the Chinese came in wave after wave overwhelming our troops. It may hold for Ladakh but not in Arunachal Pradesh. Very little effort has gone into the recording of oral history. As for the contribution of fighting men, the various states of the Northeast have become inward-looking because of the competitiveness in domestic politics. Assam remains fixated on Ahom culture while political leaders of other states, too, are more preoccupied with highlighting their effort to put indigenous cultures on a pedestal. The recording, preserving and exhibiting of their contribution to the military remains underplayed and unsung.

ANIL DAYAL/HT PHOTOS

ANIL DAYAL/HT PHOTOS

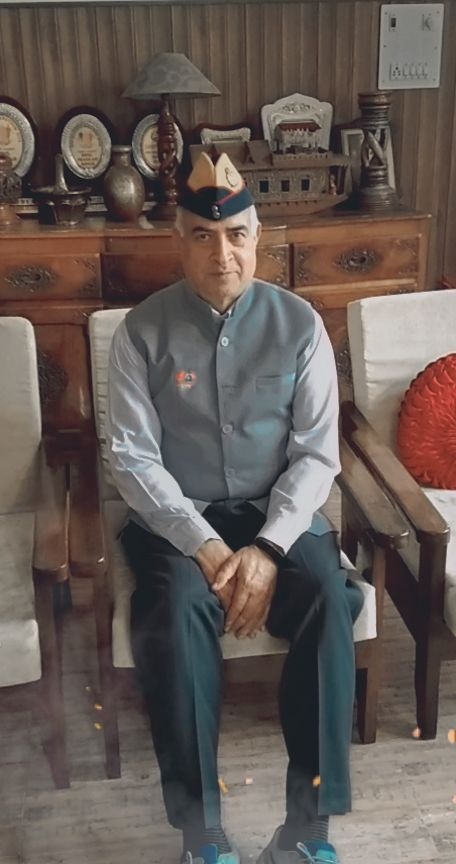

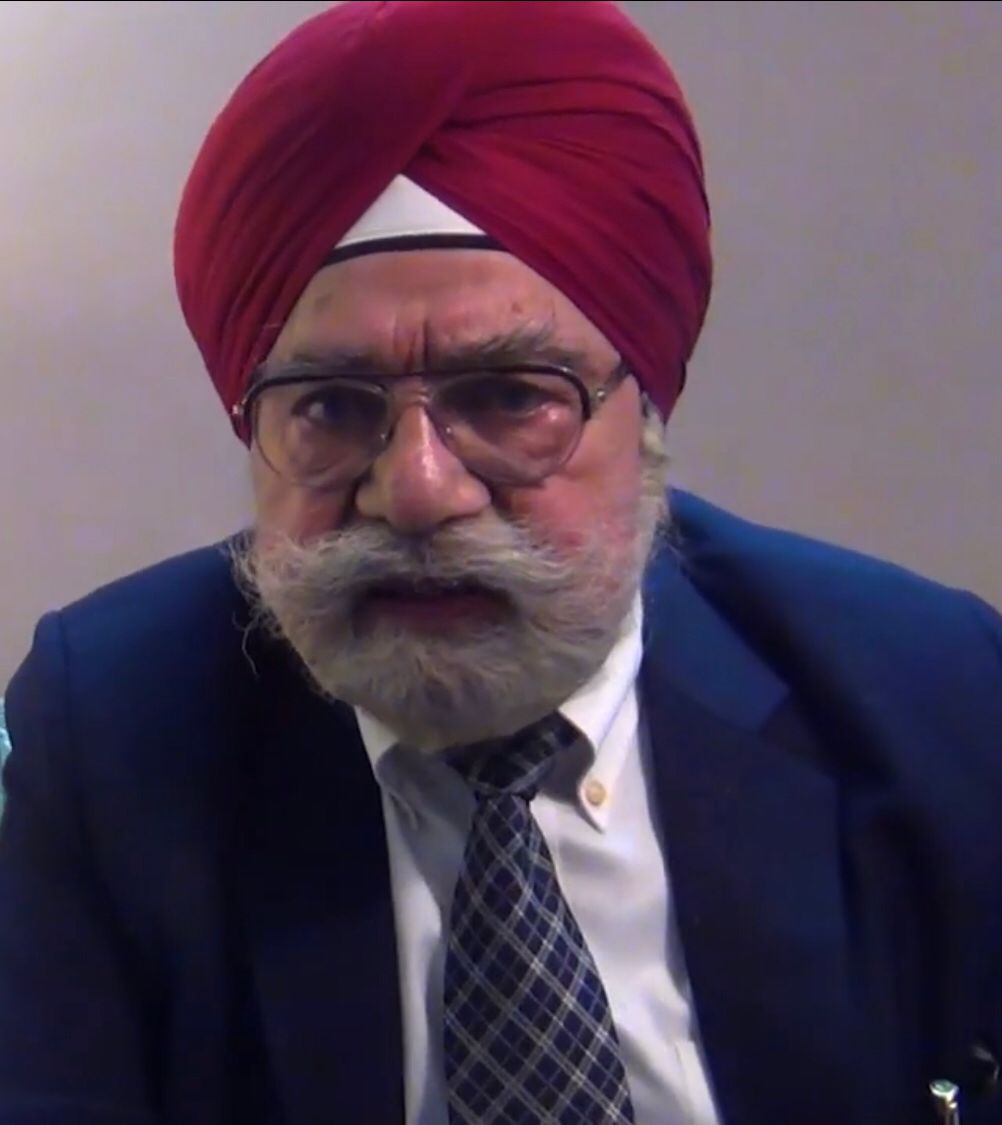

YOJANA YADAV/HT

YOJANA YADAV/HT