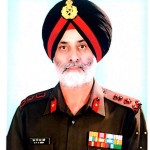

On this week’s Walk The Talk, Shekhar Gupta catches up with soldier, diplomat and academician Zameer Uddin Shah.

Shekhar Gupta (SG): Hello, and welcome to Walk The Talk. I am Shekhar Gupta and my guest today is General Zameer Uddin Shah, one of the most illustrious officers of the Indian Army. Better dressed than most people, better dressed than me, which is easy, but better dressed than most people.

Somebody who, in his memoirs, has called himself the ‘sarkari musalman’.

General Shah: Well, I am not a sarkari musalman. But I have named my memoirs The Sarkari Musalman because it is a sobriquet or a title given by the Muslim community to people who are generally government servants, when they don’t care about illegitimate demands of the community.

SG: Or stereotypes.

General Shah: Or stereotypes. That is one type. My father was called one (sarkari musalman) when he tried to implement reforms at the dargah in Ajmer. I had the fortune of meeting some young boys when I was a second lieutenant. And I tried to convince them to opt for the armed forces as a career.

SG: Muslim boys?

General Shah: Muslim boys from the Aligarh Muslim University riding club. They had come to the IMA (Indian Military Academy) to participate. And I told them the honour and glory of wearing the uniform. I also told them that we need horsemen.

Then, at the end of the talk, I asked them, how many of you want to opt for the Army. Not a single person opted. They said, “Janaab, aap to sarkari musalman hain.”

It meant that I was a government stooge trying to push the government’s agenda. So that stuck to me, and I said if I ever write a book, I’ll call it The Sarkari Musalman. But I am not one.

SG: But have times changed since then? Have young Muslims given up their suspicion of working for the government, or working for an institution like the Army, or does a lot of it still continue?

General Shah: No, I think there has been a quantum improvement. When I joined the NDA (National Defence Academy), I was the lone Muslim in my corps of 200 cadets. I am told that in one of the batches, there were 10 Muslim cadets which is a very positive sign.

Muslims, this is our country, and they too owe a responsibility for the defence of the country. So, I think it’s a healthy sign.

SG: Lt General Ata Hasnain has written for us, in fact, starting this debate that more and more Muslims should look at the Army as a career, specially officers.

General Shah: I agree.

SG: Did you feel a sense of discrimination, or did you feel like a trophy since you were the only Muslin in your batch?

General Shah: Nobody knew that I was a Muslim. At the National Defence Academy, you are given nicknames. Mine was carried by my schoolmates: Zoom Shah.

SG: Sounds like a very trendy one today.

‘No discrimination’

General Shah: You know, the nick name was not linked to any religion, caste, creed or anything like that. It was on some peculiar characteristic. For people who had protruding teeth, they are called ‘dentist’. You know, things like that. So, it was a name given to me.

And let me tell you that I faced no discrimination and I am not being a hypocrite.

SG: Which year was this, sir?

General Shah: I joined the National Defence Academy in 1964. I was 15 and a half years old. I tried to sprout a moustache to look older. And not only did I not face any discrimination, I faced affirmative action. One day, one of my coursemates, in jest, called me katua.

SG: Katua is a pejorative for Muslims.

General Shah: So, the rest of my coursemates got after him and said don’t ever say that again. So, that’s the sort of attitude that encouraged me and I was very enthused with this response.

SG: And you got it from top officers also?

General Shah: Absolutely.

SG: Was there ever any suspicion, “ki isko mat batao (Don’t tell him)”.

General Shah: Never. I was the operational officer in a division at Hussainiwala opposite Pakistan post 71. I was privy to everything. I was in the military secretary’s branch. I was the deputy chief. I mean I was privy to every national secret. There was never a time that I was told, General Shah, you go and play golf. While we are discussing, you go and… never anything like that.

SG: During the time of Operation Parakram, you were commanding a strike division that was poised to strike deep if need be. A key division.

General Shah: That’s right. And the very fact that my division was, since we were not committed on the ground, a strike division, I was tasked to lead the formation.

I was told later by General Padmanabhan, who was the chief (in my book, I have not given his name), that there were misgivings. I never felt anything. The Army, when asked, said, “We have not sent a Muslim General; we have sent the commander of the force that is committed”. And I thought that was a very good way of looking at it.

SG: So, you mean misgivings in the sense that people raised questions about the Army sending a Muslim General.

General Shah: Absolutely.

SG: But the fact is you just happened to be commanding a division that could be deployed there.

General Shah: Absolutely. The Army makes no distinction of religion, race, colour or creed. It is the commanding officer that is commanding the formation who commands.

SG: And you were in the reserve, whereas the division based in Ahmedabad was not available.

General Shah: I was in the reserve. They (division in Ahmedabad) were holding formation; they were deployed holding the border.

SG: So, what happened when you came to Ahmedabad?

General Shah: I was given the warning order by the chief personally on the evening of 28 February 2002. He just spoke to me for two minutes. He said, Zoom, get your formation in Gujarat and curb the riots. I told him, “Sir, it will take us two days”.

SG: Your formation was used to cavalry and mechanised forces.

General Shah: Well, it was a strike formation.

SG: If I do remember correctly, during General Sundarji’s time, it was earmarked to be an air assault formation. Helicopters never came.

General Shah: That’s correct. At various times, it was an amphibious division and other things. But it is a very potent division. I am very proud to have commanded it.

SG: And what happened once you were there?

General Shah: So I told him (the chief). He said, “Don’t worry. Get to Jodhpur air field. The Air Force will lay it on.” They did. Sixty flights. The complete resources of the Air Force were mobilised to move. I left immediately.

SG: So, 60 transport planes?

General Shah: Well, 60 flights. Maybe fewer planes. Sixty sorties. They were ferrying us the whole night. They were ferrying us from Jodhpur to Ahmedabad. When we flew in, I saw the whole city aflame. There were fires burning everywhere. The air field was deserted. It was dark. We landed and the deputy of the holding formation met me. He had been sent down to receive me. And I had been told that you will get all the resources you need. The resources we required was transport because we couldn’t carry them. Maps, magistrates.

SG: Because this was not AFSPA. You were in aid to civil power. So, you needed magistrates even to open fire.

General Shah: Yes, we needed that. Although a military officer, if he feels the situation (demands it), even if the magistrate is not there, he can fire. But then he needs to explain that. So, I asked Brigadier Mehra, where are the resources? He said the state government is providing it.

So, I asked for the chief secretary. He said he is abroad. So, I said, who is officiating? He gave me a number. I tried to call it, but there was no response. I decided that the only way to get things done was to go to the chief minister. I asked for a guide and I reached the chief minister’s office at 2 in the morning on 1 March 2002.

There, to my great relief, was defence minister George Fernandes. He was having a late dinner with the chief minister.

SG: Mr Narendra Modi.

General Shah: Yes. So, I had carried a tourist map because we didn’t have maps of Ahmedabad.

SG: And there were no Google maps, no Siri.

General Shah: On a tourist map of Gujarat, we plotted the trouble spots.

The assignment the Army hates

SG: I think the maps you had memorised were somewhere near the Multan sector.

General Shah: Quite right. That was working in our mind. You know, all these things I had completely forgotten. And let me tell you it’s a task that is abhorred by the Army. We don’t like to be committed to civil situations. Because they are our own nationals, they are our own citizens. And then one is to take action against them.

So, I was assured that they (the resources) would come. So I went back, received all the troops. They were large numbers, six battalions were flown in.

SG: That means, if I can take this question forward, maybe I am taking it too far. Did you get a sense that the central government had shown its keenness moving a strike division in that crucial time when Op Parakram was on, in giving you 60 sorties of the Air Force to move you there? But then you hit a wall with the state government?

General Shah: See, that would be a political statement. I think it was an administrate failure basically because of the chief secretary…

SG: I didn’t suggest, I am not going so far as to say it was deliberate.

General Shah: It was an administrative failure. The chief secretary should have been there, the officiating chief secretary should have ensured that the wherewithal for us to move into the city and all over Gujarat should have been positioned. But it wasn’t. On the morning of 2nd, Mr George Fernandes visited us at the air field.

SG: So, what happened when you reached the chief minister’s home at 2 am?

General Shah: Well, he welcomed me. He was very warm. Both showed great relief. So, I said,Saab, troops aane vaale hain, main first flight mein aaya hun (Sir, the troops are about to come. I took the first flight here).

Luckily, I had taken my vehicle and communications. So, we shared something to eat. I moved back with the assurance that things will be provided. They were ultimately provided on 2nd morning. Mr George Fernandes came to us at about at about 10 o’clock on 2nd morning.

SG: So, all of 1 March, you were just sitting.

General Shah: We were just sitting.

SG: And George Fernandes was in Ahmedabad?

General Shah: Did I say 2nd. No, he visited on the morning of 1 March.

SG: What did he say then?

General Shah: He said, you must ensure fair play; you must make sure that the message goes home that the Army has been deployed. And whatever is your requirement, we will make it up. He left after that. The transport started rolling in on the second. And we deployed.

SG: If you had been deployed on the first itself, would it have saved some lives?

General Shah: Of course, it would have saved one day of rioting.

‘A profound mistake’

SG: And did you ask people, did you reflect on it as to what happened, why did it happen? Was it deliberate, was it not deliberate?

General Shah: I did speak to a lot of people. There was a rift even in police. I was getting different versions of what actually happened. I didn’t take it. But I do know that, firstly, what made everybody angry was bringing the bodies of the karsevaks from Godhra to Ahmedabad. That inflamed passions. I think, again, it was an administrative failure, a decision that shouldn’t have been taken.

If that had not been done, probably the people wouldn’t have been so inflamed. I mean anybody would get inflamed.

SG: Was it a mistake, was it deliberate?

General Shah: I’ll not say that. I’ll not comment. I would say it’s a mistake. But you can draw your own inference from it.

SG: Would you presume it’s a mistake or would you say that the evidence of what you saw or heard suggests to you it was a mistake.

General Shah: I’ll not comment on that.

SG: You’d rather believe that it was a mistake.

General Shah: I would like to think that the leader of a state or the administrative machinery of a state did not do it deliberately. They did it as a mistake, a profound mistake.

SG: Did you find the state administration paralysed?

General Shah: Well, police was parochial, partial…

SG: Communal?

General Shah: Communal. Totally communal. The home guards, I won’t say anything. The bulk of the communards were members of Right-wing organisations.

SG: Home guards battalions?

General Shah: Home guards. They were actual participants in the rioting. I wrote that in my report. Police was non-committal. In fact, it was in the news that minority policemen who had homes in the police lines, they were burnt. So, you can imagine how much the communal violence had infected the police also.

SG: That’s what Mr KPS Gill (brought in as security adviser to the CM after the riots) also said later because he was called in and he said the problem was police.

General Shah: What really disturbed me is that, when we were deployed, I visited some areas that had sent an SOS to me. They were surrounded by mobs. The buildings had been made into fortresses. And police, instead of firing at the mobs, were firing into the windows of the buildings.

I said, what are you doing? They said, we are keeping the mobs apart. I said, then fire the other way. Why are you firing into the windows? That really shamed them. But let me tell you that whenever…

SG: They were firing into the windows of Muslim homes?

General Shah: Minority homes. And that was the excuse that we are keeping.

SG: Keeping the mobs happy.

General Shah: Well, I don’t know what they were doing.

SG: To calm them.

General Shah: Whatever it was.

SG: It’s jiu jitsu of riot control.

General Shah: Well, I won’t say that. I think it was parochial.

SG: Parochial, yes. I am also being sarcastic. These days you have to be careful.

General Shah: I am very proud that the Army, we had given strict orders that the firing has to be below the belt.

SG: And as soon as you came out, it calmed down.

General Shah: Yes, we shot down a couple of arsonists.

SG: Just two

General Shah: Two killed, 18 wounded below the belt. Large numbers were carried away and we don’t know the exact number of casualties. I think they were much larger.

SG: Casualties in terms of injured, not dead. Dead were two.

General Shah: Yes. That sent the message that the Army means business.

SG: That’s my experience covering other riots, including the anti-Sikh, you can’t call them riots, but anti-Sikh killings in Delhi. And you found that the Army came in, everybody just went home.

General Shah: That’s right.

Also Read: When Gita Gopinath batted for a GST with few slabs & talked of hope in an ‘unliberal’ world.

Uniform concerns

SG: I don’t think the Army fired at anybody or the Army arrested anybody. Once people know there is a uniformed force that means business, people are cowards, mobs are cowards.

General Shah: Yes, but I have a point here. Earlier, the olive green uniform used to be feared and respected. Now, everybody is wearing combat dress.

SG: Every security guard.

General Shah: Everyone. Even the bank guards. This is something that the Army headquarters needs to seriously take up. There is no need for camouflaged uniform for police. They need to revert to their khaki uniform. And camouflaged dress should only be the preserve of the armed forces so that it has a shock effect.

SG: Has it become a problem now?

General Shah: It has become a problem. The Army has to carry placards (that read) ‘Army’.

SG: In a flag march?

General Shah: In a flag march. We are Army. It’s disgraceful. I think action needs to be taken.

SG: I also find that every state police with ministers, they have these policemen all wearing the badge, ‘commando’. I think commando is the most diminished description in the country.

General Shah: I agree. We have stopped using it. We are using (the term) special forces in the Army.

SG: For this work in Gujarat. at that point, when did you start reflecting on writing this book?

General Shah: Well, I have been making my notes for a very long time, because I have not only been a soldier, I have been a diplomat for three years in Saudi Arabia. I have been a judge in the armed forces tribunal. And I have been an academician for five years at Aligarh Muslim University.

SG: A difficult university?

General Shah: Very difficult. I had a lot of anecdotes to write. But I never got the time. Now, people are accusing me of timing it (the book) with the elections. I mean I got hate mail saying you have political ambitions. I replied back, saying I have got none. Then, why did you write it now (the person asked). Well I said this is one year I got free, so I wrote it.

Siding with the British

SG: So, you have seen the Army change from camels to fully mechanised.

General Shah: Yes, I have seen it from the Lawrence of Arabia times to modernisation.

SG: Two eras. And your family. Your great grandparents joined the British army from Afghanistan.

General Shah: No, we migrated from Afghanistan in 1843. Basically, because of the succour given by my grandfather to 200 British women and children who were escaping. He gave them sanctuary.

SG: After the great massacre?

General Shah: After the 1843 war. Because of that, he was sentenced to death by the king, who was a nephew, incidentally, by marriage.

SG: Whose nephew? His nephew?

General Shah: His nephew. My great great grandfather by marriage. So he was sentenced to death and my great great grandfather escaped with his complete kabila and he came to India. And the Brits never forgot that. He was given a huge jagir. So, when 1857 took place, he sided with the British just like the Sikhs, all the martial races.

SG: All the races which were then called martial races by the British.

General Shah: The British-called martial races sided with the British. My children were very perturbed when I wrote this and they read it. I explained to them that, in 1857, there were no national loyalties. There was no nation.

It was tribal loyalty. My great great grandfather felt that the interests of the family would be best served by the winning side or the side that had always sheltered us. So he went to the British and we established the bridgehead over the Hindon.

SG: Oh, I see, next door?

General Shah: The Hindon, to enable the British columns to cross.

‘Army wives make incredible sacrifice’

SG: You talked about your children. You have an illustrious family.

I have you on my phone, your son Major Ali Shah on my phone. Most people will not identify him unless I say so. He plays the Army officer in the film Haider; Army officer in real life and Army officer in reel life. And he is the one who raids the house (in the film) and says the “life of my jawans, my troops is much more important than that of anybody else”.

And then you also have a brother and a sister-in-law whose numbers I have on my phone.

General Shah: I’ll tell you. Since we are following the family tradition, so my son joined the army. My son-in-law is a commodore in the Navy. He is a pilot and another son-in-law is a doctor. And, of course, the youngest, a little spoilt by my wife, he is …

SG: Always blame the wife. Let more women officers come…

General Shah: If you read (my book), the first page is devoted to my wife because I think I owe (her) a sense of gratitude. Army wives have to bear a lot. I mean they spend half their lives separate. And, in those days, there were no mobiles, you got the benefit of two letters a week. They do a tremendous job in running the household. They make a great sacrifice and it’s incredible.

SG: And your brother, more badnaam than you?

General Shah: OK, I have lived under his shadow for a very long time.

SG: Naseeruddin Shah

General Shah: I think he is the best actor of the country.

SG: So is Ratna (Pathak Shah).

General Shah: Yes, both are great actors and a wonderful team. And he has been self-effacing.

SG: You turned out to be a completely different character from your brother.

General Shah: Yes, my father gave us freedom of choice. And my elder brother cracked the IIT without any coaching. I went to the NDA. And Nasser ran away. But he still made it good. What I am trying to stress is that this talk of discrimination exists but you can surmount it by a good education.

SG: I think, on that note, that’s a very good note to conclude, but let me ask you one trick question. This feeling that you mentioned now, has it become better or worse over time?

General Shah: Feeling of?

SG: Discrimination

General Shah: Well, there was never any feeling of discrimination. But seeing what is happening in the country, I mean gau rakshaks are running amok.

SG: I believe you wrote to the Prime Minister about it.

A salad bowl country

General Shah: I did. I wrote an open letter where I was very perturbed. And I pointed out to him that it takes three generations for people to forget. If a gau rakshak murders somebody, it will take three generations for the family to forget. If a house is burnt in a riot, it will take three generations. These things are hurting the country, the unity. We are a salad bowl country, we are not a melting pot.

SG: Don’t make everybody one. Don’t give everybody the same belief system. Don’t even try to do it in the Army?

General Shah: No, we don’t try that. I mean we have got military mosques where the commanding officer comes and reads the namaz. Not that he is praying but he is…

SG: Even if he is not Muslim.

General Shah: The majority are. I mean I, being a Muslim, commanded Rajput troops. They never had any problems when I officiated in what we call the mandir parade.

SG: Similarly, you have masjid parade.

General Shah: Masjid parade, it’s a parade. So, we don’t classify on religion or anything like that. We respect the religious sentiments of our men. And when we are with the men, the Army is our religion, plain and simple.

SG: So, you would want the country to go back to that period of easy co-existence insured of becoming self-conscious about identity.

General Shah: No, we must leave it all behind. We are one nation and we should be one unified people.

SG: Spoken like a true soldier and a truly patriotic Indian. Thank you.