Our energies need to be devoted to beefing up our single-service inventories and effecting cadre reviews to achieve desirable teeth. Bringing in another level of operational command in the guise of a theatre commander is inapt for our strategic security posture and an exercise in futility. The attendant handicaps would be inadequate domain expertise of a different service theatre commander and undesirable parcelling out of air power assets.

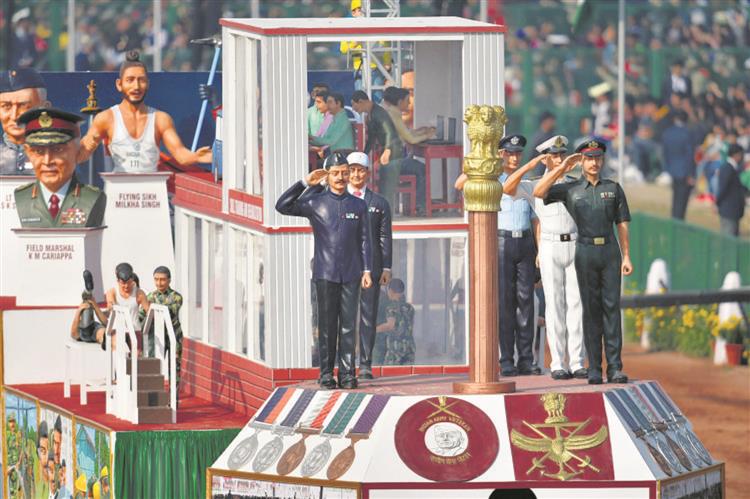

Unsuitable: Creating theatre commands is putting the cart before the horse. PTI

The Kargil Review Committee recommended a ‘first among equals’ Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) — albeit a four-star one approved by the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) in December 2019 and not a five-star one, as was desirable in a nuclearised scenario and was expected to enhance the procurement and operational integration of the three services.

But a series of missteps such as pension reforms and theaterisation bode ill for national security. The attempt by the DMA to create ‘theatre commands’ unabashedly promotes turf battles between the three services rather than leading to defence capability integration. The need for India to replace its existing seven each of Army/ IAF and three Naval single-service sectoral commands with five or so integrated theatre commands — west, north and east for Pakistan/China threats, air defence and maritime theatres — is being proposed without thinking it through.

China and Pakistan-centric operations would demand the involvement of multiple proposed theatre commands such as the Western, Northern and Eastern Land Theatres as also the Maritime and Air Defence Theatres. The need is to clearly recognise the traditional war-waging mindset and domain orientation of the Army, Navy and Indian Air Force.

The Army generally has a battle horizon of “a day’s march”, within which it sees its battle space. General Sundarji attempted to widen this to around 100 km, with his laudable mechanised ambitions.

The Navy, on the other hand, operates in a few knots per hour domain, with even gunboat diplomacy and carrier battle groups taking several days to be manifestly effective.

The Air Force is the truly strategic service, capability and mindset wise. A fighter bomber on a tactical mission is capable of achieving strategic goals, as exemplified by the timely IAF Hunter and MIG-21 aircraft strike on the East Pakistan Government House on December 14, 1971, instrumental in the capitulation of the entire Pakistani Eastern Army.

All three services have their priorities for war-fighting, derived from national security objectives and associated service doctrines. The IAF was the first to articulate an Air Power Doctrine in the early 1990s. The Navy followed up with its own doctrine and finally the Army, too.

An attempt to articulate a joint doctrine is now gaining traction, more so after the formation of the Integrated Andaman & Nicobar Command. Be that as it may, joint war-fighting procedures and norms have evolved over the years, functioning rather well indeed at the service command, i.e. operational levels.

The same has been amply demonstrated in the wars so far waged by the Indian defence forces, including in Kargil and the latest Ladakh standoff. There is no need now to try and fix a system that is not broken.

Every nation needs to adopt military organisations which suit its national ethos and threat dynamics. We do not have a five-star joint chief of staff and talking of creating theatre commands at this juncture is putting the cart before the horse.

Our energies now need to be devoted towards beefing up our single-service inventories and effecting suitable cadre reviews to achieve desirable teeth: to tail ratios. Whereas, bringing in another level of operational command in the guise of a theatre commander is inapt for our strategic security posture and bound to be an exercise in futility. The serious attendant handicaps would be inadequate domain expertise of a different service theatre commander and undesirable parcelling out of expensive air power assets.

Valuable soft skills and other command and control tools such as AWACS, AEW, flight refuelling aircraft, strategic transport/ airlift capability, electronic combat assets and other force multipliers are meant to be dynamically switched from one combat zone to another, depending on the situation. They are definitely not to be brought ‘under the command’ of one expert military leader. A novice air commander orchestrating air power in war is fraught with danger. Aping the organisational structures in the US, Israel or China (or even the puny Maldives, as protagonists have sought to) would be detrimental to operational efficiency, especially of a nation’s air force.

The prevalent career profiles in the three services do not cater to ‘maroon’ tenures in the upward hierarchical transition of a service officer. India is not yet ready to experiment with ideas such as theaterisation.

The other important deterrent against theaterisation is the dwindling force structure of the IAF, already down to 30 squadrons (and slated to reduce further), thanks to slow accretions. The dangers of parcelling out of air assets, as theaterisation envisages, need not be emphasised.

Further, the concept of a land or maritime-centric theatre is anathema to true integrated war-fighting, which is what we should strive for: a unified thinking amongst the practitioners, rather than cosmetic organisational tinkering.

If the intent is only to have a single operational commander overall, we should be aiming for a single theatre, which is what the Indian armed forces have been oriented to all these years.

Thus, the theatrisation proposal is ridden with operational lacunae which are now being sought to be thrust on an uncooperative IAF, whereas any sensible reorganisation should encompass technical weapon upgrade and efforts to better the teeth-tail ratios of our combat arms.