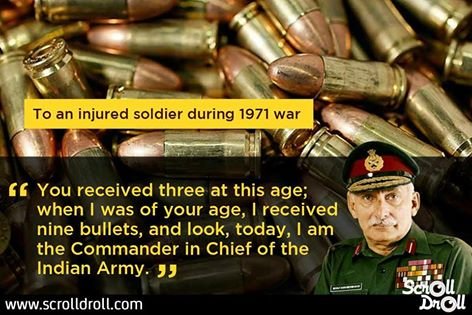

Terming hybrid warfare — using non-state actors against an adversary nation — as “not the best option”, Indian Army chief General Bipin Rawat on Wednesday said this tactic was causing more damage to Pakistan than to India.

“Any nation that has attempted hybrid warfare against an adversary has finally been the sufferer. Today, Pakistan is facing that brunt,” Rawat said while delivering a lecture on “Challenges of hybrid conflict in 21st century”.

“They (Pakistan) supported something in Afghanistan but after the imbroglio was over, what happened to those people (the jihadis)? This hybrid warfare launched by them (Pakistan) has actually started affecting them more than it is affecting us,” Rawat said.

However, he warned that the proxy war by Pakistan is there to stay despite all the things and despite India’s effective tackling of it.

Responding to a query as to why India, even after suffering for decades, does not launch offensive hybrid warfare against Pakistan, Rawat said it is not the best option for India, and emphasised that India is satisfactorily countering this warfare directed against it. “Paying the other fellow exactly in the same coin may not be the best option. A stone that is thrown in the air comes back to your head.

“Before we launch the hybrid warfare in the offensive-defensive domain, we should be prepared to see what will happen to those people once the objective is achieved. What you do with those people?” he said.

While he underlined that India does have the capability to launch an offensive hybrid warfare or even “strike across” at those perpetrating the hybrid offensive against it, the army chief said for that the Indian leadership must be clear as to how far the country can go if an escalation happens.

“India will have to carefully work on the escalation matrix as to how far it was willing to go if escalation happens,” he added.

He said to counter such operations by Pakistan, which include a propaganda on the social media, various Indian forces and agencies need to work together in close coordination.

Rawat said India can utilise its soft power with friendly nations to isolate the terror-exporting nation and offered that the Indian Army can help the country expand its soft power in many ways.

Speaking on the Kashmir situation, Rawat said that sustained pressure is needed to tire out the militants instead of wrongly believing after a peaceful year in the Valley that lasting peace has returned.

“When things become comfortable, we would go into this limbo thinking that peace has returned, not knowing that every time the peace returns, the nexus has utilised this period to rebuild their capacities and strength. And therefore sustained pressure is required,” Rawat said.

“What I am trying to highlight is that you get one successful year and you say let’s give peace a chance. That is I think a fault that you have been committing.

“If you think that just after having one successful year you should give peace a chance, that may not be the best option. You should have repeated successes and then think of giving peace a chance. And that is what we are doing now. Let us look at tiring the other side,” he added.

He also rued that the army faces flak even for taking a tough action against those pelting stones at it.