It was in the late seventies that a potential nuclear threat from Pakistan started to emerge. Gloved in frequent denial and deliberate leaks to create a psychological effect, Pakistan was desperate to acquire nuclear capability in order to conceptually offset India’s asymmetric conventional advantage. The concept of nuclear red lines did not seriously emerge at this time although this has today become a major factor in our operational doctrine. Through the eighties, the Indian mechanised forces were expectedly gung ho with their numerical and qualitative advantage. Deep objectives were sought and planned for, with destruction of the Pakistan war machine as the prime intent of battle.

What really assisted in the adoption of some offensive concepts was the early decision after 1972 to construct the ditch cum bund (DCB), a continuous anti-tank obstacle through the plains sector of J&K, Punjab and the Rajasthan-Punjab border. Although linear obstacles have been known to have been breached many times in history, they do prevent surprise and early loss of territory. Defensive stance can then be lighter with dependence on reserves that are available for both defensive and offensive operations. Progressively, the offensive content of the doctrine for the plains, obstacle ridden and desert terrain has thus witnessed an increase. The same could not be said of the mountains where the doctrine remained largely defensive. Till 1991, except for the raising of one mountain division for the Kameng sector in the East, no accretions took place signifying how much more the commitment of India was towards the threat emanating from Pakistan.

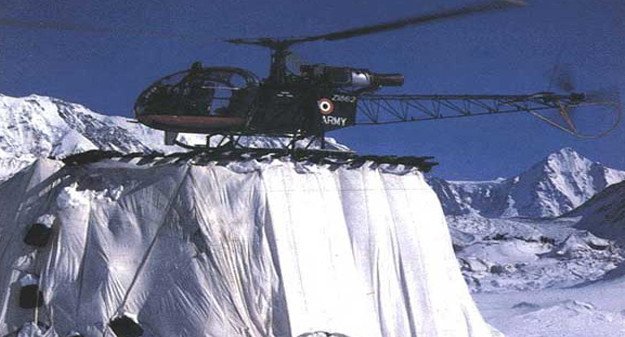

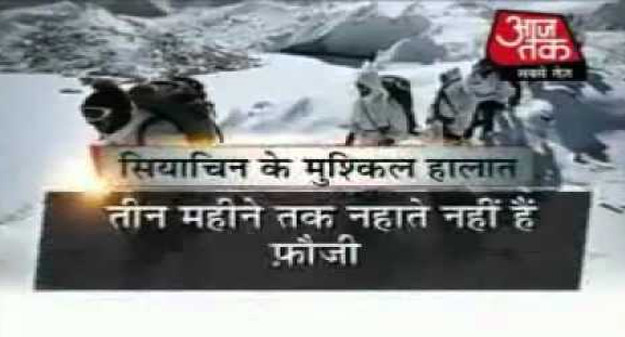

From 1978 to 1984, India witnessed increasing intimidation by Pakistan in the Siachen area. It was an area with an un-demarcated LoC . Left to the Pakistan domination it would have meant a broader swathe of territory to give depth to the Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK)–China border and thus assist in their collusive strategy. Rightly, in one of the finer strategic decisions, the Indian Army occupied the Saltoro Ridge and denied the Siachen Glacier to Pakistan. An additional division was raised to take charge of the LoC in Ladakh and a new terminology came into being – the Actual Ground Position Line (AGPL) in the general area of Siachen. It is important to remember that Siachen’s strategic importance cannot simply be wished away; its holding is even essential for the defence of Leh.

In 1987, the Indian Army ventured on its first out of area operation; Operation Pawan was perceived as necessary to retain the regional influence, but assessment about the way the operation would pan out went completely awry. Admittedly, an unclear aim and an uncertain strategy ensured that 30 months of deployment resulted in little gain except in refining the infantry’s basic tactics and getting many units battle inoculated under fire. In late 1988, another out of area operation (Operation Cactus) led to the scuttling of an attempt to overthrow the legitimate government of Maldives. By any yardstick it was a highly successful operation launched with uncharacteristic decision-making which was speedy and correct. If anything, India did learn from Operation Pawan that launching out of area operations or deploying forces in assistance of another government should only be done with extreme care and full war-gaming of contingencies. Without a matching strategic and logistics air-lift capability, taking decisions on out of area operations will always be fraught with danger.

The threat scenario came to a head in 1989 when Pakistan took full advantage of the prevailing chaos in the world order and the political and financial instability at India’s centre to launch a proxy war in J&K and instigate the population to revolt. This was far bigger than Operation Gibraltar attempted in 1965 and was a result of the elaborate strategy of Zia ul Haq and the Inter Services Intelligence (ISI). The aim was to tie down India in a ‘war of a thousand cuts’, instigate separatist tendencies, restrict the achievement of India’s aspirations. Although the conflict was centred on J&K, the intent was to target different parts of India. By 1991 the proxy war was already raging through Kashmir. The Indian Army undertook responsibility for countering the proxy war, which over a period of time has evolved into an effective hybrid war against India. The Rashtriya Rifles (RR) was raised for the purpose of fighting the insurgency to relieve the main Army units and formations from the responsibility. However, the campaign has evolved into a mixed responsibility model.

The period 1972 to 1991 did not see a conventional conflict but the threats kept the Indian Army deeply involved in low intensity conflict of different kinds which kept its ranks actively involved and sufficiently inoculated. It was the well thought through structural changes, the regular induction of military wherewithal, reorganisation of support organisations such as Defence Research & Development Organisation (DRDO) and Ordnance Factory Board (OFB) plus a score of other progressive changes which kept the Indian Army sufficiently geared for combat across the spectrum of conflict. The one single fault that one could pin point now was perhaps the lack of sufficient attention towards infrastructure at the northern borders, something we rue even today.

Multiple Threats And Challenges In The Path To Modernisation, from 1992 to 2017

In the nineties, the main theme in the threat scenario was terror and its manifestation in J&K. The Northeast also remained unstable. On the conventional front, China was in the process of its modernisation and involved with high percentage economic growth. Agreements not to disturb the status quo at the Line of Actual Control and remain in engagement helped create a more congenial relationship with China. However, Pakistan continued to sponsor a proxy war in J&K ensuring at the same time that it kept the threshold just below India’s limit of tolerance. The degree of success gained in neutralising foreign and local terror groups through the nineties was a remarkable achievement leading to the showdown at the Kargil heights.

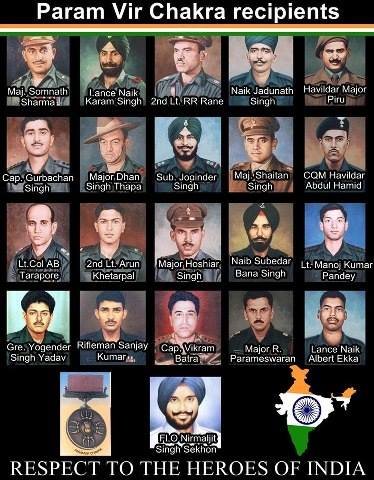

The Kargil conflict (Operation Vijay) was a high octane war fought by the zeal and leadership of India’s new generation officers and soldiers. However, it was a landmark event in that India and its Army were taken by surprise even as the operations revealed glaring intelligence, equipment, ammunition and organisational frailties. The fact that Pakistan could re-energise the Valley simply by forcing out a full formation from there, as a response force did prevail on the minds of India’s strategic planners. The strategic space lost in North Kashmir took almost three years to regain.

.jpg)

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS