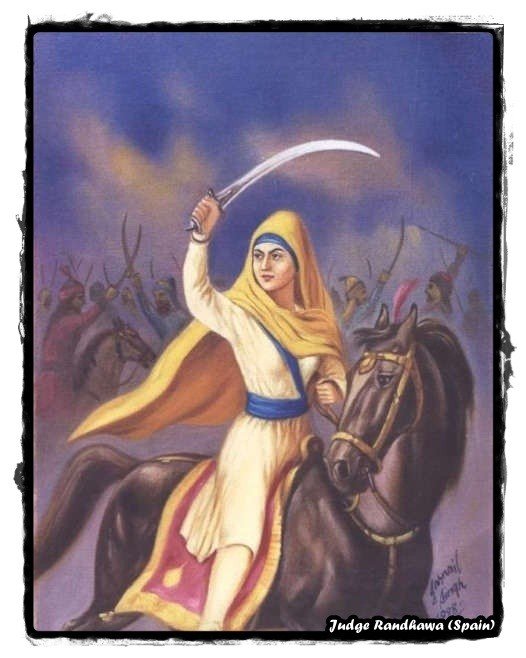

Mai Bhago also known as Mata Bhag Kaur was a Sikh woman who led 40 Sikh soldiers against the Mughals in 1705.

She killed several enemy soldiers on the battlefield, and led a life of true Sant Sipahi in every aspect. She was the sole survivor of the battle of Khidrana, i.e. Battle of Muktsar fought on 29 December 1705)

In her childhood, Mai Bhag Kaur was called Bhag Bhari, which means “fortunate”. On being baptized, she was named Bhag Kaur. In the Sikh history, she is known as Mai Bhago.

She was born in a well known village, Jhabal, near Amritsar in year 1666.

She was the daughter of Malo Shah, son of Bhai Pare Shah. Her grandfather and Pare Shah’s brother, Bhai Langaha, had served under Guru Arjan Dev and Guru Hargobind.

Bhai Langaha had helped Guru Arjan Dev in the construction of Harmander Sahib and was one of the five Sikhs who accompanied Guru Arjan Dev when he went to Lahore for martyrdom.

The young Saint-Soldier

She visited Anandpur with her father in 1699 when Guru Gobind Singh created the Khalsa and was baptized along with other members of her family

She had inherited from her family ideals of bravery and courage.

Faith, truth, and fearlessness were her ornaments.

She had a well built body and started learning the art of warfare and horse riding from her father. She came to know that some Sikhs of her area had deserted Guru Gobind Singh at Anandpur Sahib and renounced his guruship in writing (Bedava).

The governor of Sirhind was planning a big attack on Guru Gobind Singh at village Dina where he was staying after the Battle of Chamkaur.

She could not hold herself, and in zeal to serve the Guru, she, the great heroine, said to her husband, “let us lay down our lives for the Guru who has sacrificed his father, mother and four sons for the Sikh faith. We must not sit idle when innocent lives are being bricked alive.”

She motivated the ladies of the area to challenge those deserters. These ladies dressed themselves as soldiers and wanted to proceed with Mai Bhago.

She said to the deserters, “Guru Ji has sacrificed his family and comforts for our freedom. We should not hide ourselves like cowards. Everybody has to die. Why not die like a brave person? If you don’t join me, I shall take a party of women and die for the Guru.” They got armed and they took the oath to die fighting and not to retreat from the battlefield. All of them marched to help the Guru and seek his forgiveness, under the leadership of Mai Bhago Ji.They were also informed that the Mughal forces, under the command of the governor of Sirhand, were proceeding towards the Guru.

In 1704 the city of Anandpur Sahib, the residence of Guru Gobind Singh Ji was under extended siege by the combined forces of the Mughal army and Hill chiefs. The siege took its toll and the meager provisions were completely exhausted, with the Sikhs having to live on leaves and bark from the trees.

Within the Sikh ranks there was a group of Jats of the Majha region, they had had enough and they made up their mind that they wanted to escape and leave Anandpur Sahib. After much deliberation they made their way to the Guru, and their leader Maha Singh told him of their desire to leave. Guru Gobind Singh Ji understood their situation but asked them to stay and fight, but all his persuasive arguments fell on deaf ears, they were resolute, they wanted to leave.

With no alternative Guru Gobind Singh Ji with a heavy heart asked them that if they truly wished to leave then they must write a disclaimer and have it signed by all the deserters claiming that they no longer belonged to the Guru, and the Guru no longer belonged to them. Obviously we can never understand the hardship the Sikhs had to endure and the desperate situation the Sikhs were in but even so, when we think of the great sacrifices made by Sikhs like Bhai Mani Singh, Bhai Taru Singh, Bhai Mati Das, Bhai Sati Das and Bundha Singh to name but a few it is hard to understand what possessed the Majha Sikhs to put pen to paper and write a disclaimer that “Guru Gobind Singh Ji, we are no longer your Sikhs and you are no longer our Guru,” it must go down as a most shameful episode in Sikh history.

The deserters were from the Majha region and one of the villages in this area was called Jhabal, and in the village lived a woman named Mai Bhago. She was known for her faith and courage and when she saw the 40 Sikhs approaching in the distance she went out to meet them. She asked news about Guru Gobind Singh Ji, and when she heard their sorry tale her blood boiled. She could not contain herself, she charged them with cowardice and a lack of faith in their Guru. She felt, as did the other women folk of the area that they had brought shame on their region. Mai Bhago was determined to wipe this stain of infamy of the Majha sikhs. She told all the women folk not to be hospitable to the Sikhs, she shamed and censured the Singh’s for their cowardice.

Mai Bhago donned on men’s clothing and told them that either they stay behind and look after the children or they try to make amends and return with her to the Guru. Ashamed by their act of desertion they vowed to put things right and mounted their horses and set off towards Frozepur.

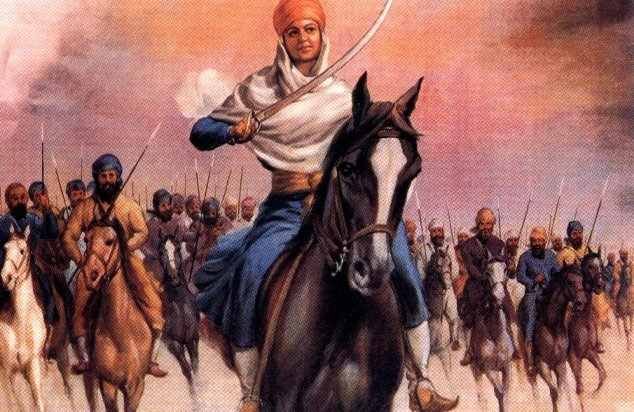

Knowing that the enemy Wazir Khan was advancing to attack the Guru, Mai Bhago’s group took up positions near a place called Khidrana. As the enemy forces came close the Sikhs pounced on them, a fierce battle ensued; although heavily out numbered the Sikhs attacked with ferocity and many were killed on both sides. The dust raised by the battle alerted Guru Sahib Ji who by this time had vacated Anandpur Sahib, he joined his Sikhs on a sandy hill (tibbi) and shot arrows on the enemy. As the battle raged Guru Sahib Ji mounted his horse and led his contingent from the west. The enemy could not stand a sudden attack on its left flank and after sustaining heavy loses withdrew leaving the dead and dying on the battlefield.

Guru Gobind Singh Ji dismounted from his horse and surveyed the scene. He saw one of his Sikhs lying wounded and recognised him as Maha Singh, the leader of the 40 deserters. Guru Ji sat beside him and put his head on his lap and wiped away the blood and tears from his eyes, just as a father would a son. Guru Ji was greatly impressed and pleased by his Sikhs. “Ask whatever you will, the house of Guru Nanak is open to you” spoke Guru Ji but Maha Singh only had one thing on his mind, the letter of desertion. “O Lord of all the heavens, if you are in mercy then please forgive me and my companions for our betrayal, and all that I pray for now is that you tear up the letter we handed to you.” The all knowing Guru had kept the letter on his person knowing full well that it would be needed, Guru Ji took it out and tore it in front of Maha Singh.

“You have redeemed yourself here and in the hereafter.” The forty deserters who lay dead in the battlefield were blessed by Guru Sahib Ji as the chali mukhtay –the forty liberated ones. A grand gurdwara now stands at the site of the battle, known as GurdwaraTibbi Sahib, Mukhtsar.

Mai Bhago in the meantime was also laying in the battlefield wounded. Guru Ji blessed her for her courage and fortitude in leading the Sikhs into battle and regaining their honour. In time Mai Bhago recovered from her wounds and remained in the Guru’s presence after the battle. Mai Bhago followed Guru Sahib Ji to Nanded. In 1708 when Guru Ji ascended the heavens Mata Ji settled at Bidhar about 200 km from Nanded where she lived to a ripe old age. Mata Bhago Ji is held in the utmost high regard by Sikhs and considered a saint. Her spear and musket that she used in the battle at Mukhatsar is still preserved at Takhat Sri Hazur Sahib, Nanded.

Gurdwara Tibbi Sahib is associated with the Tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh Ji. This place is situated in high sandy mound (tibbi means a small hillock). Guru Sahib chose this place to stay on reaching Muktsar as it provided a very good view of the area. When the battle between the Forty Muktas and the Mughals was in progress, Guru Ji helped his sikhs by shooting arrows at the Mughals from this place. The birthdays of Guru Nanak Dev Ji, Guru Gobind Singh Ji and shahidi purab of Guru Arjun Dev Ji are celebrated with great fervour here. Besides, the Magh Mela is organized on the 12th and 13th of January to commemorate the sacrifice of the Forty Muktas. Diwali and Baisakhi are also celebrated with enthusiasm.

The Guru praised the bravery of Mai Bhago. She told the Guru how the forty deserters had fought bravely and laid down their lives.

The Guru asked her to go back to her village as her husband and brother had also obtained Shaheedi in that battle.

She expressed her desire to become an active saint-soldier and stay in the service of the Guru. Her wish was granted and she stayed with the Guru as a member of his bodyguards.

She accompanied the Guru to Damdama Sahib, Agra, and Nanded and lived there until the Guru left this world.

After the Guru’s death, she left Nanded for Bidar.

She lived there & preached Sikhism till end of her life.

She was a symbol of bravery and courage. Her life history and organization skills against odds will always be a milestone in Sikh history.

Red Corridor forces have mostly suffered when they encounter large groups of insurgents.

Analysing a tragedy for whatever reasons must begin with an expression of regret.

That’s exactly how I look at the situation where the nation has been left frustrated yet again with a heavy loss in the security domain.

Losing 25 police personnel in circumstances much like in the past inspires little confidence in the ability of Central armed police forces and of the intelligence agencies that support them in the Red Corridor.

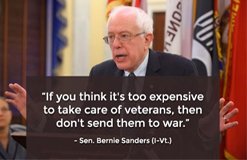

Amid all the patriotic fervor that accompanies the loss of uniformed personnel, the public also deserves to know why this happens so often. While doing so the colour of the uniform one has worn must not be evident; only then will justice be done. To make this into an “us versus them” affair within the uniformed services would be inherently unfair.

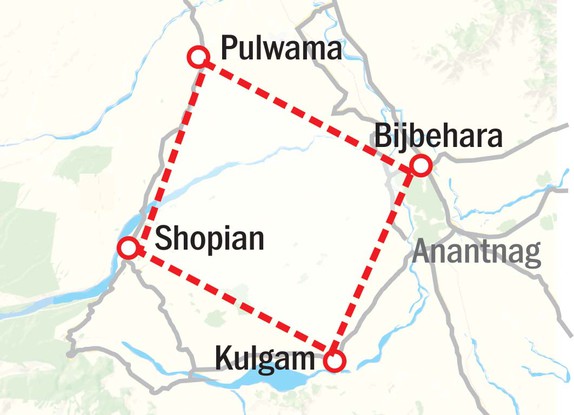

Even as I write an encounter is in progress in Kupwara where the Army has suffered losses. Such losses in the administrative realm, of camps and perhaps convoys, doesn’t absolve the Army and Central forces in Kashmir from the many blunders which have occurred in the recent past.

Sukma is nothing short of a tragedy. I insist on calling it that since innocent policemen doing their job and being martyred as they were not trained adequately to do that job is indeed a tragedy.

Citing former US defence secretary Donald Rumsfield, the phrase “known knowns” is most applicable here. Almost everything which goes into making such a repeated tragedy is a “known” in terms of past analyses, and we are fully aware that it is a “known”. There are some “knowns” that can’t and won’t change unless transformational decisions are taken, but it’s important to keep the public informed.

The Central Reserve Police Force has been delineated as the core or lead force to take charge of counter-insurgency operations (CI ops) across the country. Was this Union Cabinet decision, based on the recommendations of the Kargil Review Committee and Group of Ministers, correct? Is it something that should be reviewed?

Analysts are far happier quoting the decision than questioning its wisdom, or the absence of implementation. When such decisions are taken, they should be based on the capability of a force or its potential. If the latter, then the means to acquire that capability must also be delineated and orders issued. By merely recommending the CRPF as the lead force for CI ops without examining its structure, manning pattern and command and control, the Kargil Review Committee perhaps erred substantially. However, the purpose is not to assign blame; a decade and a half down the road experience itself would have repeatedly shown that in its current format and makeup it is unfair to give the CRPF such a responsibility. The “known knowns” of the force mentioned by every analyst in the past three days needs a brief recount. Chasing nimble tribal guerrillas armed to the teeth who are fighting a “son of the soil” insurgency in a terrain they know like the back of their palms isn’t really a joke.

CRPF jawans are often 50-60 years old as the retirement age in the force is 60. It will be unfair to question it as I am unaware if the force has laid down an age limit for deployment of personnel in the Red Corridor. If not, then it is essential, and units must be restructured as Red Corridor units.

The Army’s Rashtriya Rifles is a fine model of a CI force to examine and improve upon.

The manning pattern, under which senior CRPF positions are occupied by Indian Police Service officers is too flogged an issue to repeat. The point to emphasise is that institutional awareness of weaknesses in the operational realm can’t be expected from a hierarchy completely inexperienced in training, planning or execution of such operations anytime in their service. To be parachuted into one or more star ranks and suddenly bearing operational responsibility and the lives of so many personnel under care is inherently unfair both on the IPS officers and the CRPF.

Harping on this is like begging the question, as nothing is likely to change. It is best to work around it and look at other ways of potential optimisation. Leadership, training and equipment are the three areas which need to be reviewed, other than the senior leadership question.

Most fighting entities will inform you that the best welfare for warriors is to ensure they are fully enabled in their quest to inflict maximum casualties on the adversary, and prevent casualties unto themselves. This is best done through training and professional stocktaking.

Some Red Corridor forces like the Andhra Pradesh Greyhounds have proved their capability beyond doubt, but such excellence is a drop in the ocean compared to the magnitude of the problem.

The Army’s Para SF units, particularly the ones that have operated in Sri Lanka and the Northeast, have institutional experience and strength. There are enough veteran officers and men who could be tapped professionally to impart their knowledge.

Institutions like the National Police Academy are centres of excellence which must be involved in analysis and lesson-learning in a substantive way. The plethora of experience that the CRPF and state police forces possess is itself not little.

The circumstances surrounding the Sukma event, however, do not inspire any confidence on the basics that those involved in such operations must have. Everything here is supposed to be tactical, including having meals.

Troops deployed on operations do not eat at the same time, and not without establishing security through observation posts, sentries and the like. There is obviously a real need to return to the basics, and to do so repeatedly.

Red Corridor forces have mostly suffered when they encounter large groups of insurgents.

Obviously, one of the banes of such operations is contact-based command and control and getting the sub-unit to respond beyond just returning fire. I am not sure whether training on this is ever carried out. CRPF units are most usedly to platoon-based functioning. Even the best Army units may find it difficult to have a full company-based response in the face of such situations. The fact that a full company can come under enemy action at a single time is itself a reflection of questionable field tactics. If this is to improve, egos must be shed. Smaller teams can train with Greyhounds and other successful police outfits, but if a full sub-unit response is necessary, it should imbibe the Army’s functional culture.

The immediate upgrading of equipment is vital. The Union home ministry has a very efficient procurement machinery. It must look at rotary aviation resources for recce and response. The Mine-Protected Vehicle is an imperative, and funds can’t be the reason for not provisioning this.

While the intelligence services have secured India quite well over the last many years, tactical-level intelligence in the Red Corridor still seems to be highly questionable.

I laud the BSF’s concept of G sections of its units. In all my experience, I have not found more competent intelligence personnel at the tactical level.

This is something that the CRPF should examine closely.

The writer, a retired lieutenant-general, is a former commander of the Srinagar-based 15 Corps. He is also associated with the Vivekananda International Foundation and the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies.