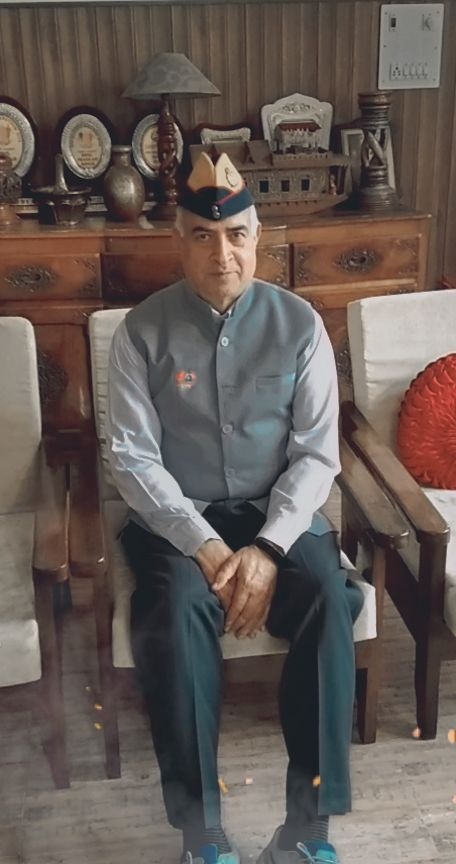

Maroof Raza

Strategic Affairs Analyst

There are some uncanny similarities between the Pakistani intrusions in the summer of 1999, on the northern half of the Line of Control (LoC) — commonly referred to as the Kargil sector — and the Chinese intrusions at multiple points along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) east of Ladakh this summer. But there’s also a big difference. The LoC was a marked and accepted boundary with Pakistan, and hence Pakistan’s intrusions were illegal. This gave India considerable international support. But regarding the LAC between India and China, New Delhi’s arguments are not

watertight, even though the world is still very much in India’s favour.

And while Pakistan’s intrusions in 1999 took place as troops withdrew in the winter months from the higher reaches of the LoC — as agreed — the Chinese took up their positions now when the Indian Army dropped its annual Op-Alert to check their deployments along the LAC, due to the overzealousness to follow the government’s guidelines on anti-Covid-19 measures. The Chinese, however, used this Indian lapse to build up considerable force levels opposite Indian positions on the LAC, and worse still, they intruded in areas that were traditionally not held, as every hilltop and valley isn’t held physically. The Chinese army is still holding on to most of their gains, regardless of the optimism among the apologists for the government.

But a similarity between the experiences of the Kargil conflict and the current Chinese intrusions is that our tools of gathering external intelligence haven’t delivered. Whether it is the ‘shepherds’ or satellites that the government’s well-funded intelligence bodies were banking on, they’ve either failed us, or those in charge of gathering these inputs have glossed over the inputs. Either way, our brave jawans have again paid with their lives.

And as was the case in the initial stages of the Kargil conflict, the swift use of PR by the intel agencies once again led to their friends in the media to blame the CDS and his lot, for the ‘intelligence lapse’ against the Chinese. A similar line was adopted by the shadowy men in our establishment when the Kargil surprise had raised the call for scapegoats, when the media went on to say ‘that the blame lay with the then Army chief for gross negligence of Pakistani build-up and intrusions.’ But the new appointment of CDS is not responsible for gathering external intelligence, even now. This has to come to the armed services from the multiple organisations there to gather and pass on their inputs. Otherwise, why have them? Two decades after the Kargil conflict, our commentators cannot still surely be arguing who must be responsible for gathering information from across our borders?

However, then (in 1999) and now, a bigger failure has been our inability to read or assess the intentions of our adversaries. In the current situation, it is now clear that neither those who are Mandarin speakers nor those who know the Chinese and their ways had fathomed what was on Beijing’s mind. More so, when the plainspeaking politician, George Fernandes, pointed a finger at the Chinese, as India’s Defence Minister in the mid-1990s, to say they presented a bigger threat to India, and not Pakistan. Some of us agreed with him then, and continued to say so, but the policy makers on Raisina Hill in Delhi had other illusions. But just as the Kargil shock had led to additional military deployments north of Kashmir and west of Ladakh — with the raising of a new corps in Leh and an additional army division added to it — the Chinese intrusions have led to the move of at least two extra divisions plus armour and mechanised forces along the LAC. Apparently, they will be there to stay, for the long haul.

While during the Kargil conflict, troops were rushed in to throw out the Pakistani intruders — with little time even for troops to acclimatise — then and now, there is also a similar situation of insufficient weapons and equipment for our frontline soldiers, though it wasn’t because of that the men of 16 Bihar had to resort to hand-to-hand fighting in the Galwan valley. In the Kargil conflict, our men fought against many odds to regain those icy heights, and fight they surely did. But the Chinese aren’t going to be a pushover, more so, unlike Pakistan in 1999 that was a divided house — between a much surprised Nawaz Sharif and an aggressive General Musharraf — Chinese President Xi Jinping and the Communist Party of China (CPC) have an aggressive agenda on multiple fronts in Asia.

But our armed forces do have many new weapon platforms now, to the credit of the NDA and UPA governments, from expensive fighter aircraft to long-range maritime drones and attack helicopters. While these fit more into the plans to show your muscle to the adversary with ‘military force multipliers’, a lesson from the Kargil conflict was the need to equip our infantrymen well to fight in those icy heights — and Aksai Chin too has tough high-altitude terrain — with air and artillery support on that hazardous front. It’s now clear that this stand-off with China will go into the winter months. For that, we need to equip a force level five times that we have in Siachen. It would also require us to shift the focus of our forces from being Pakistan-centric to at least be equally balanced when facing the threats from two fronts. China has built up Pakistan’s capabilities for precisely such a time, to present us the two-front threat.

More importantly, India must now quickly create two ‘strike corps’ by using the existing manpower better — since new resources may be hard to come by — with one each to be launched anywhere northwest of Nepal and east of Bhutan, to divide the attention of China’s western theatre command that’s responsible for their entire land borders with India. By using the multiple military commands facing China, India could spring many surprises, if the political order so desires. However, budgetary re-allocations will have to be made now (not next year) — to give these strike corps alpine equipment for a war in the high Himalayas — if the assertions of our ministers are anything to go by.

As we have seen until now, the initiatives adopted — diplomatic, economic and military — haven’t been effective enough. Are we running out of options because we have failed to learn lessons from the past? Is there a sense of a 1962 déjà vu? Perhaps to prevent that, our leaders may do well not to raise the rhetoric, because when the people’s expectations go up, then a nation can be driven into a conflict, the cost of which is always high.