The Guru’s life and teachings provide a vision for the creation of a sustainable and egalitarian community, which has great relevance today

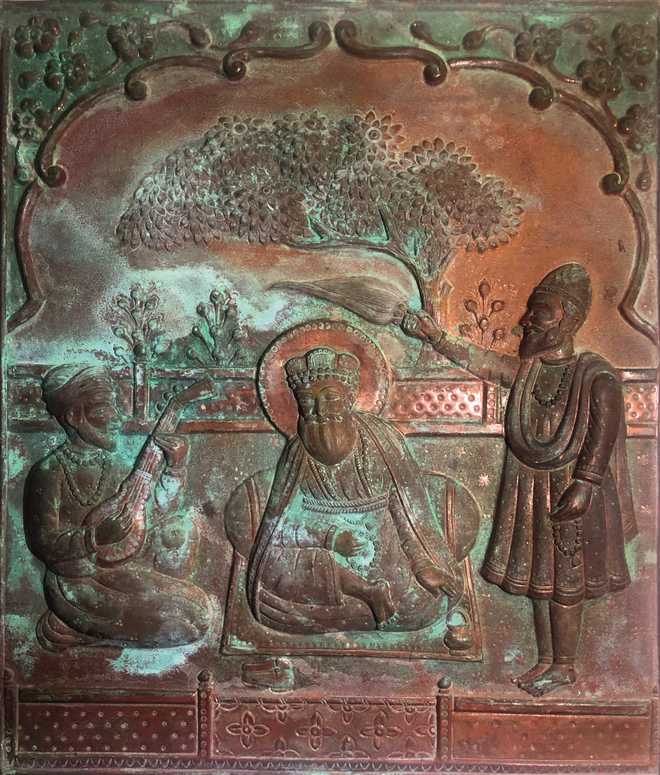

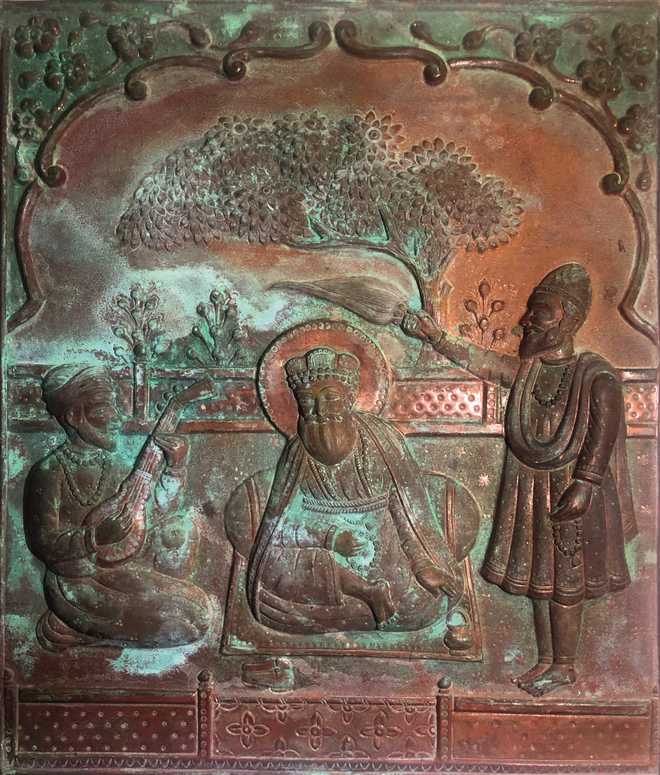

Baba Nanak with Bhai Bala and Mardana. Repousse by Sujan Singh on copper, of the mural panel from the Bairagi Thakurdwara at Ram Tatwali, Hoshiarpur

Baba Nanak with Bhai Bala and Mardana. Repousse by Sujan Singh on copper, of the mural panel from the Bairagi Thakurdwara at Ram Tatwali, HoshiarpurNadia Singh

Guru Nanak is hailed as a champion of humanism. However, a little known aspect of his philosophy is its distinct “eco-sophical” tradition. This tradition has profound lessons in chartering a path of sustainable development, especially in the face of the current socio-ecological crisis facing humanity. Guru Nanak’s understanding of the socio-economic and ecological constructs of society mirrors the concept of the “three pillars of sustainability” — social equity, environmental protection and economic well-being. It has been recognised by international agencies like the United Nations that these three pillars are fundamental to the creation of inclusive, environment friendly societies. Guru Nanak’s writings reveal that he had an astute knowledge of the interdependence between the social, ecological and the economic realms of life. He provided a new vision to his followers, wherein all the three realms work in harmony with each other. Guru Nanak was a lover of nature, and recognised the inherent link between the human and the non-human world. At the same time, he was cognisant of the societal ills associated with greed, materialism and appropriation of wealth. He established an alternative model of development based on community sharing, voluntary service and pooling of resources in the society he established at Kartarpur. The most fundamental aspect of his vision was its focus on egalitarianism. He strove to protect the interests of the most marginalised and vulnerable sections of society.

Nature, part of the Creator

Guru Nanak’s thinking on environment differs from other Bhakti philosophers of the time, who treat Nature as primarily an object of worship. In contrast, his writings focus on nature as a part of the creator, implying that caring for nature and its preservation is essentially a form of worship. Several passages in Guru Granth Sahib elucidate this fact. The most famous of these is, “Air is our teacher, water our father and the great earth our mother; day and night are the male and female nurses.” Guru Nanak also displayed an astute awareness of the “dialectical” relationship between the human and the non-human world so that one cannot survive without the other. He writes, “You yourself the bumble bee, the follower, the fruit and the tree. You yourself the big fish, tortoise and the cause of causes.” This understanding of the relationship between humans and Nature is reflective of ideas in modern day ecology. In his famous aarti, he evokes the image of the entire universe as participating in worship and compares the grandeur of creation with the small scale of the Hindu form of worship of lighting an aarti (flame).

Guru Nanak’s philosophy displayed a keen insight into the inter-linkages between the social and ecological aspects of life. He was a revolutionary thinker who recognised that all humans are essentially composed of matter, “Born out of flesh, in flesh does man live”. He condemned the purification rituals espoused in the Manusmriti as meaningless and merely a means to give divine sanction to the injustice and humiliation by one section of the society of another. Even as a child, he challenged the practice of caste superiority and ritualism, associated with the practice of wearing the Hindu sacred thread, janeu. He asked the priest, “What difference would it make?” When he did not get a satisfactory answer, he refused to do so and proclaimed, “It is righteous deeds that distinguish one person from another.” He went on to say, “Make compassion the cotton, contentment the thread, continence the knot and truth the twist. This is the sacred thread of the soul and if thou has it, O priest then put it on me.” Guru Nanak emphasised that all humans are created equal and should be bestowed with equal rights, irrespective of caste and gender.

Champion of equality

Guru Nanak was born in a pre-capitalist society. However, he was keenly aware of the fact that materialism and appropriation of wealth are hurdles in the creation of an egalitarian, ecologically friendly society. He denounced moh (materialism) and lobh (avarice) as the primal sins and equated them to pollution. “Pollution of the mind is greed; the pollution of the eyes is to look with covetousness upon another’s wealth; the pollution of the ears is to listen to slander.”

He was a vociferous critic of the imperialist tendencies of the Mughal empire. Addressing his acolyte, Bhai Lalo, he wrote, “Babar leading a weeding array of sin hath descended from Kabul and demanded by force the bride, O’Lalo.” He also expressed anguish at the treatment of women following Babar’s invasion, while being incarcerated in Sayyidpur prison, “The Muslim women read the Koran and in suffering call upon God, O’Lalo. The Hindu women of high caste and others of low caste may also put in the same account, O’Lalo.”

Nanak went on long travels (udasis), but did not advocate asceticism. Instead, he focussed strongly on giving back to the community. He wrote, “Asceticism lies in remaining pure amidst impurities.” At the end of his first udassi, around 1521, he built a community in Kartarpur as a model of a sustainable society. It was based on the three pillars of sangat, pangat and langar to promote community ownership, voluntary service and pooling of resources. Guru Nanak said, “They alone who live by the fruit of their own labour and share its fruit with others have found the right path.” The practice of langar became one of the hallmarks of the community in Kartarpur and promoted social solidarity. It also acted as a direct blow to the caste system and untouchability. In a fitting tribute to Guru Nanak, the langar has become the cornerstone of the Barcelona World Parliament of Religions held every year.

Guru Nanak’s life and teachings provide a vision for the creation of a sustainable, egalitarian community, which has great relevance in today’s times. Unfortunately, his legacy has not been sufficiently followed in praxis by the Sikh community. His vision of holistic development through the integration of social, economic and ecological realms is yet to be realised. As a whole the Sikh community has still to become the model of a casteless, egalitarian, community driven, environmentally conscious society, which Guru Nanak had envisioned.

— The writer is a lecturer in Economics, Northumbria University, UK