The strategic import of the Balakot air strike will not be lost on the Pakistan army, which will be compelled to rethink its strategy in view of India’s willingness to use air power in the interests of national security. For the first time in decades, the Indian security establishment has overcome its hesitation to use air power in the proxy war waged by Pakistan.

Mindset: The traditional diffidence to use air power, anticipating retaliation, has been a stumbling block.

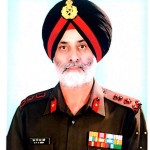

Air Marshal Brijesh Jayal (retd)

Former Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, South Western Air Command

THE Balakot air strike by the IAF’s Mirage-2000 aircraft has strategic security implications that transcend its immediate tactical significance. A formation of the IAF aircraft penetrated Pakistan’s air defences and successfully completed its mission despite the fact that the neighbouring country was on high alert after the Pulwama attack. Clearly, the IAF’s mission planning, tactics and execution proved too good for Pakistan’s air defence system. This is not for the first time that Pakistan’s air defences have been found wanting. They were also caught by surprise when US commandos neutralised Osama bin Laden in 2011, virtually in the neighbourhood of Pakistan’s military establishment. The question arises: why would the Pakistan Air Force, which is professionally recognised, neglect its air defences when it considers India an enemy with a strong air force?

Let’s rewind to the 1962 war when the Chinese army was threatening the Assam valley. At that time, White House intelligence reports had concluded that if India were to use combat air power, this would have a significant impact on the ground war. Yet US Ambassador John Galbraith advised India’s Defence Minister and the Prime Minister against the use of offensive air power, for fear of Chinese air force retaliation on Indian cities (such as Kolkata) and economic targets. Based on this advice, India failed to commit the IAF to an offensive role. The IAF top brass, too, failed to prevail upon the political leadership, even though air combat forces were available, joint structures with the Army were in place and there were the obvious limitations of the Chinese air force operating out of high-altitude airfields in Tibet.

This diffidence to use air power, anticipating retaliation, has somehow embedded itself in the psyche of the Indian security establishment. The mindset that the use of air power is escalatory manifested itself again during the Kargil conflict when the IAF was limited to operating within our own airspace and specifically forbidden from crossing the Line of Control (LoC). One keeps hearing similar sentiments expressed by security experts during debates in the electronic media.

The Pakistani military establishment has been quick to exploit this defensive Indian mindset and the window of opportunity it affords them. Knowing well, especially after the 1971 war, that India will always have an edge in conventional warfare, it has chosen the proxy war route to bleed India in Jammu and Kashmir ‘with a thousand cuts’. As this approach has paid them dividends and the Indian security establishment has come to live with the inevitability of the proxy war, Pakistan has built considerable ‘assets’ in the form of separatists and radical groups in J&K and other parts of the country. That it has well established training facilities like Balakot shows that this security template is there to stay. Indeed, it has used this template in Afghanistan as well. Going nuclear has added to Pakistan’s confidence of being able to deter India while relentlessly pursuing their objective of targeting India and keeping its security forces tied up through the proxy war.

The strategic import of the Balakot mission will not be lost on the Pakistan army’s GHQ in Rawalpindi as India’s willingness to use air power to further its national security interests compels the former to rethink its strategy. It also puts a burden on them to commit resources and professionalise their air defences.

There are lessons for us as well. For the first time in decades, the Indian security establishment has overcome its hesitation to commit air power in the proxy war waged by Pakistan. One can only hope that having overcome this psychological barrier, the national security establishment will now be open to tapping the full potential and flexibility of air power in the interests of national security and not try to confine it to the Theatre Commands.

Even as Wg Cdr Abhinandan Varthaman has been released, there are three questions the nation must ask itself and not be satisfied with woolly answers: Why was the IAF pilot flying a dated MiG-21 when his adversary was in a contemporary F-16? Why is the IAF so hopelessly short of its combat strength with many squadrons equipped with aged and obsolete aircraft? And can we stop politicising the Rafale purchase and let the induction process move ahead so that the morale of the IAF is not dented?