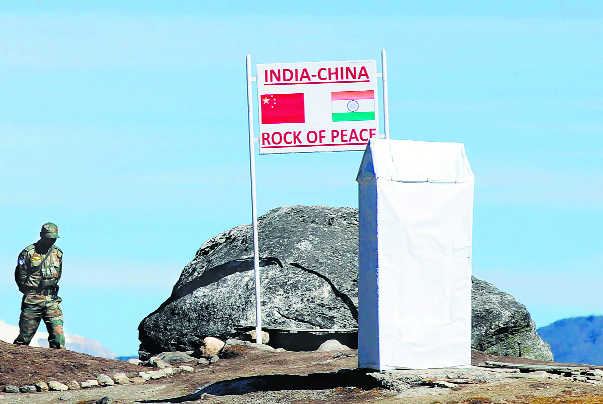

‘Humbled’ China may go for ‘salami slicing’ of disputed areas

Keep the peace: Confrontation shouldn’t be met with jingoism; a sure recipe for a flareup.

Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain (retd)WITH the reported presence through winter of enhanced strength of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of China opposite Doklam, with improved operational and logistics infrastructure, is a Chinese military standoff or more with India almost a surety in 2018? The end of the 72-day standoff over Doklam was hailed as pragmatic; an example of political maturity and military astuteness by all. That was the need of the hour for China. It was about to conduct its five-yearly signature political event, the Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) from October 18, 2017. Xi Jinping’s image would not be very high if China was seen to be in the middle of an ugly border spat with a neighbour, which could turn violent with an innocuous trigger. It was also hosting the BRICS Summit at Xiamen, and, presumably, could not be seen to be in an armed border standoff with one of the members. If China did actually pull back from the standoff, albeit reluctantly and without clarity and with those events now over, what holds it back from pressing its claims in the next season and instigating a similar situation? The Army Chief, Gen Bipin Rawat, to his credit, did mention that we have to be prepared for more such standoffs with China, which could resort to “salami slicing” and muscle flexing by it to nibble away at areas claimed by it and under dispute with India.The 19th CPC was about bigger things. It set the tone for China’s future superpower status by 2050 and capability to win wars. Doklam was just an aberration, but for Jinping’s personal ego and that of the PLA, it was enough of a setback, temporarily papered over. India won fulsome praise for its ability not to back down in the face of severe intimidation. This model is being examined by various nations in East and South East Asia, perhaps much to the embarrassment of the PLA and Xi himself. So, is China likely to be in a hurry to retrieve lost prestige from the perceived slight or remain pragmatic and patient? It needs to be remembered that in the leadership provided by Xi in the last five years and more, diplomacy and economic leveraging have played a major role. Yet the restructuring of the military and Xi’s ability to push new strategy has dominated the scene. In its stance towards the disputes in the South China Sea and with Japan in East Asia, China has continued to follow the “Three Warfares” principles adopted in 2003. These relate to intense psychological operations, media manipulation and legal warfare designed to manipulate perception of target audiences on claims put forth by China. The manifestation of this, in practice, really commenced more robustly under Xi although “war under informationised conditions” was a strategy first mooted in the early ’90s. This is the broad strategy it has played out in Ladakh over the last seven to eight years with “walk in operations” aimed to see the capitulation of Indian leadership under persistent claims pressed through military pressure, albeit without firing a shot. It could always have triggered an armed standoff and hoped to secure its claim lines under imposed robust duress on the Indian forces. Yet, China has long been the exponent of Sun Tzu’s concept of winning wars without fighting; “to subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill”, wrote Sun Tzu, thus giving Chinese military thought a supposed pearl. In Xi’s assumed slight due to Doklam there exists the greatest potential of employing Sun Tzu’s age-old philosophy juxtaposed with the modern concept of “Three Warfares”. This should rest some minds which assume war fighting as the only realm of Chinese strategy. Xi should, and probably will, not be in any hurry to restore his pride after the slight at Doklam because he has gained enough stature after the 19th Congress of the CPC. The enhanced military presence opposite Doklam is a part of the three warfares strategy. However, winning without going to war in the context of the Doklam involves two things. First is to build the disputed road unhindered on the territory claimed by it, but currently technically under Bhutan’s control; second, to establish a closer diplomatic relationship with Bhutan as a breakthrough and wean it away from Indian “stranglehold”, much as Nepal has been weaned away.For India, it will be a win-win if it can continue to retain Bhutan’s loyalty and thereby play up the Indo-Bhutan Friendship Treaty of 2007 for mutual consultation and prevention of use of each other’s territory for inimical purposes. Thus in Bhutan lies the key and the focal point. If China really wishes to follow the wisdom of its ancient sage with the technology of the modern times, it will focus on Bhutan, while continually intimidating India through low-level military standoff, but high-energy media and psychological war with persistence on claims to keep the legal pressure at a high, almost akin to the South China Sea dispute. Military brinkmanship will, no doubt, form a part of it, but the area where China is likely to be more cautious and probably review its strategy is in the field of media manipulation. Its information strategy in 2017 backfired as state mouthpieces, The Global Times and People’s Daily just could not make that difference. In a ham-handed show of information warfare, China failed to intimidate India, placate Bhutan or win support internationally. That is a sphere it will now concentrate upon, although it is an area much more difficult to convert to advantage. Thus while keeping our powder dry, which must anyway be a part of considered prudence, it is the sphere of information warfare and local regional diplomacy in which India must prepare itself much better. The feasibility of China displaying a trailer of its cyber capability focused on a sphere of Indian military or non-military activity also remains a reality for which India must prepare itself. 2018 may well be the year when threats of war fighting may be overtaken by threats of cyber and information warfare. The last reminder: Bhutan will remain the key to the standoff and the retention by India of the current relationship will be the decisive factor. The last time, Indian strategic thinking hit the bull. If the basics are right it will do so again. The writer is former GOC of the Srinagar-based 15 Corps