China is facing economic uncertainty, given the crisis in the real estate sector, which accounts for 35 per cent of its economy.

THE External Affairs Ministry’s latest annual report describes relations with China as “not normal”; in fact, they are adversarial. The government will keep China blanked out, even though for the foreseeable future, it will remain a perennial rival, competitor and threat. Significantly, Global Times, a state-run Chinese newspaper, recently published an opinion piece praising India’s strategic confidence and remarkable achievements in recent years. The article, written by Zhang Jiadong, Director of the Centre for South Asian Studies at Fudan University, Shanghai, also acknowledged India’s economic growth, improvements in urban governance and a shift in attitude towards international relations, notably with China. The opinion piece lauded India’s foreign policy under Prime Minister Modi, highlighting the nation’s multi-alignment approach and bolstering ties with major global powers such as the US, Japan and Russia, while displaying a nuanced stance on the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

A two-decade-old comparative study by the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), New Delhi, titled ‘Will India Catch Up With China?’, had noted: a) both will compete for resources and market influence; b) it’s unlikely that they will again become mortal enemies; c) likelihood of war and conflict minimal; and d) India must close the economic gap. The CPA quoted Goldman Sachs’ projection that if India recorded a growth rate of 8 to 9 per cent, it could catch up with China by 2050. In its own forecast, the CPA says that it is not a matter of catching up with the growth rate but how to come abreast in terms of the GDP, for which India must grow 9 to 11 per cent, which will not be easy due to poverty and low per capita income even by 2050.

A Foreign Policy article in 2003 had enquired, ‘Can India overtake China?’ and concluded that India might edge past China in the future, but the CPA gave it a low probability. Recent projections of an enduring political stability are very promising.

India is chasing China’s economy. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has pledged that in his third term, India will be the third largest economy after the US and China. He also said that India will be a developed country (read catch up with China) by 2047. This is akin to a hop, skip and jump to ensure a minimal growth of 9-11 per cent.

China is facing economic uncertainty, given the crisis in the real estate sector, which accounts for 35 per cent of its economy; however, its economy has tripled since 2008. Although Xi Jinping is virtually the President for life, his fetish for sovereignty and national security has led to political turbulence, evident in the sacking last year of a foreign minister, defence minister and nine Generals — five from the strategic Rocket Forces, who were lawmakers.

Alfredo Montufar, head of Geopolitical Risk, Beijing, said last September in Mumbai that China’s perception in the developed world is the lowest, courtesy its wolf-warrior diplomacy. He noted that China was going into the below-potential growth period from 6.5 per cent in 2023 to 3.5 per cent in 2030 and 1 per cent in 2050.

So, in the catch-up game — China catching up with the US, India with China, Pakistan with India, and so on — are there political, diplomatic and military expedients in the India-China matrix available to India to fix the asymmetries and find equalisers? That is the billion-dollar question.

China’s economy and per capita income are six times larger than India’s; its defence spending is over three times of what India spends on defence.

Clearly, the CPA report of 2003 was off target in its India-China forecast of the minimal likelihood of war and conflict and the unlikelihood of both becoming mortal enemies again.

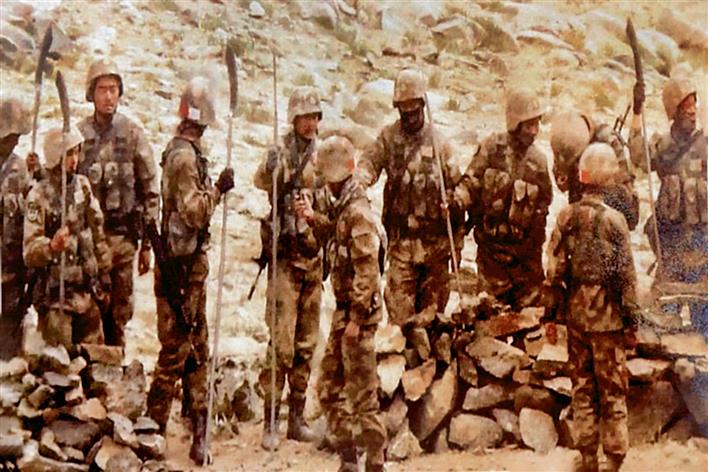

A report prepared in 2022 by the China Study Group, New Delhi, said Indians had replaced Americans as the people whom the Chinese hated the most. The Galwan clash, after four decades of peace on the LAC, ended with unprecedented Indian casualties and officers and soldiers taken captive by the PLA without the use of firearms. Later, Operation Snow Leopard exposed the frail civil-military relations and abrogation by the political executive of higher direction and guidance of war when the two armies were on the ‘brink of war’.

India’s trade deficit with China was $101 billion last year. Twenty rounds of military commanders’ talks and several bouts of politico-military diplomatic parleys have made China look taller and thrown overboard the theory that trade and talks reduce friction and facilitate conflict resolution. At a recent seminar that I convened in New Delhi, ‘Catch Up To China: On Fixing Asymmetries and Finding Equalisers’, no innovative solutions were offered due to the fear of annoying China and escalating the conflict. There were no buyers for conducting any game-changing operation similar to Snow Leopard on land or at sea or exploiting China’s Malacca dilemma.

That India will need to spend a minimum 5 per cent of the GDP on defence to create deterrence against China within a decade was highlighted, as also ensuring that the economy grows by 8-9 per cent to just close the gap with China by 2030. Diffidence and deference have to yield to determination.