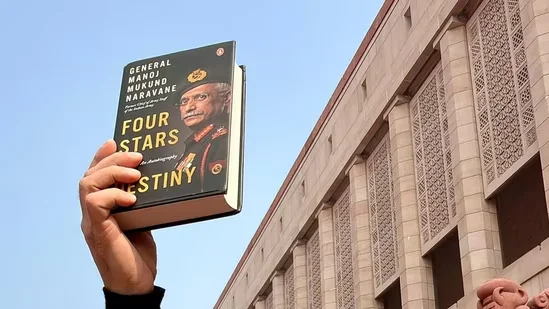

A book by General MM Naravane, India’s former Chief of Army Staff (COAS), has dominated Parliament proceedings this week, with Leader of Opposition Rahul Gandhi being stopped from citing its contents to question PM Narendra Modi and his government over their China policy. It’s not published, so can’t be cited, according to Rajnath Singh, who heads the defence ministry where it’s reportedly pending for approval since 2023.

Story behind writing ‘Four Stars of Destiny’

He has also shared how he decided to write it at all. “There is a story behind writing this book. I had no intention of writing a memoir or an autobiography,” he told web channel Lallantop in an interview in April 2025, a year after the book was originally supposed to be published.

“Penguin (publishing house) had published a book on the late General Bipin Rawat. I went to its book release in March 2023. People who had come from Penguin, jokingly I told them that ‘you aren’t publishing a book of mine’. In response, they asked, ‘Have you written a book?’ I said no,” he recalled.

“I told them, ‘If you say so, I will write it,’ to which they said, ‘Yes sir, it will be a matter of pride if you give us this opportunity to publish your book’,” the retired officer said. “And like that, by the way, this process started for me to write a book.” He said the satisfaction he has got by writing the book “is enough”.

Moments of national security crisis do not always collapse because of poor intelligence or

weak soldiers. Sometimes, they fail because no one at the top is willing to own the decision

that history demands. General Manoj Mukund Naravane’s account of the tense night on the

Kailash Range in eastern Ladakh offers a stark illustration of this failure—one where political

leadership chose ambiguity over accountability.

As Chinese tanks advanced to within a few hundred metres of Indian positions, local

commanders did what professional soldiers are trained to do: report, warn, and seek orders.

An illuminating round was fired—a warning, not an act of escalation. It failed. The Chinese

kept moving. The situation had crossed from routine friction into imminent confrontation.

At that point, the Chief of Army Staff did exactly what civil–military doctrine requires.

Naravane reached out to the apex of India’s political and strategic leadership: Rajnath

Singh, Ajit Doval, Bipin Rawat, and S Jaishankar. His question was simple, direct, and

unavoidable: What are my orders?

The answer, devastatingly, was silence.

The Cost of Not Deciding

India had imposed extraordinary restrictions on the use of force—orders not to open fire

without clearance “from the very top.” Such political control over escalation is

understandable in theory. Nuclear-armed neighbours, fragile diplomacy, and international

optics demand caution.

But caution is not the same as paralysis.

By withholding a clear directive at a moment when tanks were rolling forward and minutes

mattered, political leadership effectively outsourced the risk downward—without authorising

the authority needed to manage it. This is not civilian supremacy. It is civilian abdication.

In crisis management, not giving an order is itself an order. It tells commanders: absorb the

risk, take the blame if things go wrong, and preserve political deniability at all costs.

Plausible Deniability as Strategy

Naravane’s account exposes a deeper pattern: the preference of political leadership to

maintain strategic ambiguity not toward the adversary, but toward its own military.

If firing is prohibited without top clearance, then the top must be prepared to give—or

explicitly refuse—that clearance in real time. Otherwise, the system becomes structurally

dishonest. Publicly, leaders project resolve. Privately, they avoid decision points that could

later demand explanation in Parliament, the media, or history.

This culture explains much of what followed Galwan: opaque disengagement terms,

euphemisms like “buffer zones” and “friction points,” and the quiet normalization of territory

where Indian patrols no longer patrol. Political leadership could claim peace while the

military absorbed the strategic loss.

Ownership would have required standing up and saying one of two things:

- Yes, hold your ground even if it escalates; or

- No, de-escalation is the priority, even at tactical cost.

What happened instead was worse than either choice.

Soldiers Need Orders, Not Alibis

Professional armies are built on clarity of command. Soldiers can execute dangerous, even

unpopular orders if they know those orders are lawful, deliberate, and owned by the state.

What corrodes morale is not restraint, but uncertainty—especially when restraint is imposed

without responsibility.

Naravane’s repeated calls, his frustration as minutes ticked by, and the absence of direction

from civilian leaders reveal a system more concerned with post-facto narratives than real

time leadership.

The irony is stark. Political leaders insist on absolute control over the trigger, yet hesitate to

touch it even when the situation demands a conscious decision. This leaves commanders

suspended between doctrine and reality, forced to manage escalation without authority.

The Larger Question Naravane Opens

Naravane’s memoir does not merely recount an episode; it raises an uncomfortable question

for Indian democracy: who bears responsibility when political leaders choose not to

choose?

Civilian control of the military is a cornerstone of democracy. But control without

accountability weakens both democracy and defence. When political leaders demand

restraint, they must also accept the strategic consequences of that restraint—territorial,

operational, and psychological.

By failing to give clear orders on the Kailash Range, India’s political leadership preserved

short-term deniability but inflicted long-term costs: constrained military options, altered

ground realities, and a precedent where hesitation at the top becomes institutionalized.

History is rarely kind to indecision masquerading as prudence. And in national security,

silence at the top is never neutral—it is a choice, with consequences borne by those farthest

from the microphones and closest to the guns.