TOTAL SHARES

New Delhi: Brigadier Varinder Singh’s unfinished handwritten manuscript was meant to be an account of the Indian Army’s capture of Pakistan’s Quaid Post from Sonam, where one soldier out of 10 survived an avalanche last week.

The brigadier died in 2012 doing what he loved best -playing basketball in a Noida court.

Lance Naik Hanamanthappa Koppad, of 19 Madras, now tenuously hanging on to life at the army’s Research and Referral Hospital in New Delhi, was flown down from Sonam. He continues a tradition set nearly 30 years back by Major Varinder Singh and his band of brothers from the 8 JAKLI (Jammu and Kashmir Light Infantry).

In June 1987, Varinder Singh was the major who led the company of selected soldiers from his 8 JAKLI battalion up the ice wall from Sonam. Sonam is at 19,600 feet and surrounded by treacherous crevasses.

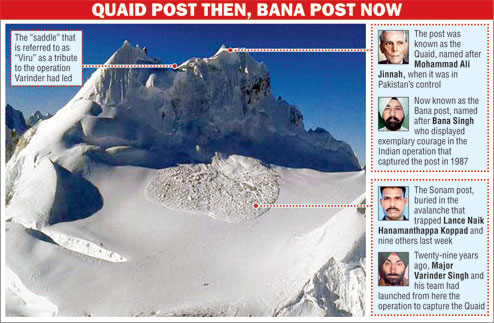

Their objective was a Pakistani position at more than 21,000 feet – 1,500 feet above. It was of strategic import. From the post named after their Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistani troops had a clear view of the glacier, and an Indian Army battalion headquarters at 16,000 feet.

They could monitor helicopter movement and pick out Indian soldiers and patrols. They could direct artillery fire. In May 1987, they killed nine of 13 Indian soldiers led by Lt Rajiv Pande, who were attempting to do what Maj. Varinder Singh finally succeeded in doing a month later.

The soldiers overran the post and turned the guns, which were aimed at India from the south to the north, to aim at Pakistan.

Subedar (now honorary captain) Bana Singh led the assault, finally killing the six injured Pakistani soldiers with grenades thrown into the shelter in which they were yelling from pain.

Bana Singh was awarded the highest gallantry award, the Param Vir Chakra, and is paraded every Republic Day and Army Day as the soldier to be adopted as role model for the Indian Army.

Varinder, the major who rose to be brigadier, was awarded the Vir Chakra for his leadership. The “saddle” in the ridgeline that overlooks Sonam, where the 10 soldiers were buried in the avalanche, is often referred to as “Viru” after him.

“It is such a waste, this war in the mountains,” his wife, Anita Singh, says in their house in southwest Delhi. She remembers the telegram from her husband’s comrade, Maj. R.K. Singh, through the Snow and Avalanche Study Establishment (SASE) the next day that informed her of his injury.

“Viru OK. Stop. Came down. Stop. Had two drinks. Stop. Now in hospital. Stop. OK,” it said.

Anita reached the military hospital at Leh from Srinagar, where she was then living, on the morrow. Varinder recovered after 17 stitches and 15 days in the hospital.

Shrapnel from a Pakistani artillery fire had pierced Varinder’s torso and chest when he was leading the operation. Varinder writes in his account of a Subedar Sita Ram, radio operator, who used to describe Pakistani artillery shelling in words like ” Ravan ke dus laddoo gire, char airburst aur baki ground-burst. (Ten laddoos from Ravan have fallen, four were airbursts and the others hit the ground).”

After Pakistan lost the Quaid Post, they brought down heavy artillery on what used to be their own position to evict the Indians.

“What happened was ironical,” recalls Anita. “Because it is so cold up there, the blood around his wounds coagulated quickly and stopped him from haemorrhaging”.

Subedar (honorary Lieutenant) Girdhari Lal, who was in “Viru’s” team and now helps Anita run her business, recalls that the officer came down the hill using his right hand to staunch the wound and stop the bleeding.

Writing in The Telegraph on Wednesday, Lt Gen. Syed Ata Hasnain, former commanding officer of Indian troops of the Northern Siachen Glacier, estimates that the country spends about Rs 5 crore of taxpayers’ money to keep Operation Meghdoot running daily. Gen. Hasnain retired as military secretary in the Army Headquarters. Few would have more in-depth knowledge of the costs of military operations.

This does not take into account wages and allowances. One former financial officer in the defence ministry estimates that New Delhi spends up to Rs 1,500 crore a month to sustain troops on the Siachen Glacier.

This includes fuel to keep helicopters flying, transportation, specialised garments and equipment, food, medicines, oxygen cylinders, Hapo (high altitude pulmonary oedema, that is the commonest ailment up there) bags that are sometimes used to turn milk into curd, boots, snow scooters and weather forecasting machines. For every battalion posted up there, there are three in training to acclimatise for the cold and the altitudes.

The real costs, however, take the heaviest toll in the minds and bodies of the men and the women through personal physical presence at those heights or through emotional bonds, like Anita’s.

Those bonds are so strong that they sustain after death. Yesterday evening, in her flat, Subedar Girdhari Lal and former Subedar Major (honorary Lieutenant) Onkar Chand Bakshi were there to share her story with this newspaper.

The former junior commissioned officers (JCOs) were two of Maj. Varinder Singh’s handpicked and trusted soldiers for the assault to capture the Quaid Post.

“We all wrote our last letters and carried them in our pockets at the time of the assault,” says Bakshi. “So did Sahab”. Major Varinder Singh had instructed his men to write their last letters in case they did not survive. He wrote one to Anita too.

“I wanted to read it but he tore it and threw it away,” she laughs now. “‘No point,’ he said, ‘because I’m still living, in case you haven’t noticed’.”

The 8 JAKLI troops were training for the operation since March of that year. Three attempts had failed. But Rajiv Pande’s men had managed to drive pitons on the cliff up to 10 metres short of the saddle.

The rope was passed through karabiners (coupling links) all the way down to the base just behind the Sonam post. It still took the men two days to find the rope that was buried after snow blizzards. They hoisted themselves to the saddle in two nights and then Varinder and his men fought their way along the knife-edged ridge to take out the Pakistani post.

Girdhari Lal recalls that something actually went wrong. The initial plan was to go around the Quaid Post and take out its base camp that sustained the Pakistani men at the top. But the plan was changed, probably because the Pakistanis got wind of it, and it was decided to go for the Quaid Post straightaway.

The Quaid Post was targeted by Indian artillery fire from Sonam and another position behind it. The shelling had to be stopped for the men to clamber over.

“Our beards and moustaches had gone white from the snow. And the snow had gone black from the shelling and the firing,” says Girdhari.

Since the Indian soldiers under Varinder were to get into Pakistani-controlled territory, they were told to ensure that no one was captured alive.

” Humlog LTTE walon ki tarah cyanide capsules leke gaye the,” says Bakshi. The orders were to commit suicide if there was the possibility of capture.

Anita listens to the account in stoic silence. The understanding that her husband was ready to die like a guerrilla has been with her for years. But she did not know then.

Beautifully written in a slanting hand, in his never-to-be-finished manuscript, Varinder recalls the orders: “It was late evening when I reached and went straight to the Commanding Officer’s hut. Late Col A.P. Rai, UYSM, was in the throes of a head massage but it was not difficult to see a mix of remorse, anger and revenge on his face. A man of few words but he always conveyed his point implicitly. He came to the point right away – Quaid had to be captured and ‘revenge’ to be taken. The Gorkha and a Rai at that, had taken his decision though the generals conveyed it to us much later… I for one know I was going to lead the attack – there was no doubt in my mind.”

Varinder, a fifth-generation army officer, actually started rehearsing the assault at Sonam, at the base of the Pakistani post. Two soldiers were killed in the rehearsals, probably going down into crevasses. The bodies were not found.

Despite the training, Sepoy Jasbir Singh rolled down from the knife-edged ridge on the night of June 24 to the Pakistani side. He was probably shell-shocked from the firing by an Indian post, says Bakshi. “I brought him up on my shoulder,” he recalls.

“While we were going up to Quaid, we saw the bodies of five soldiers from the aborted attempt a month back,” says Girdhari. The cold and the snow preserve bodies well.

Alpha company, that Varinder led, climbed from the head of the rope to the saddle, trusting their crampons (metal plates with spikes fixed to the boots) on a sheer 10-metre ice wall. The basketballer showed the men how to do it. For three days, they had little to eat or drink.

“Sahab had given a strict order,” says Girdhari Lal. “No one was to go down (to Sonam). There were no bunkers. We burrowed in the snow. Our minds were wandering,” he says. “They used to hallucinate a lot,” says Anita.

“We used to ask one another’s names just to check that the brain is functioning. This happened to us earlier too. Once when I was trekking to Bela (another post), I lost my way in a barfila toofan (snow blizzard). We just had to wait it out. Then on another occasion, Rifleman Balwan Singh went from our tent to the cookhouse in an igloo to get food. He did not return,” says the honorary lieutenant.

At the saddle, Varinder and his men burnt camphor to heat their rifles. The rifles, mostly clunky old 7.62 SLRs at the time, would often not fire because the triggers jammed in the cold.

At 4.30 in the morning of June 26, 1987, the men crawled out of the saddle to link with an advance party of four that included Subedar Bana Singh.

The rest is history.

Since then the Indians have not been able to come down. The Pakistanis have not been able to go up. And a lance naik in the Research and Referral hospital battles for life after being given up for dead.