Since the terrorist attack in Uri in 2016, India has worked to ensure it utilises its full claim under the Indus Waters Treaty. Several stalled projects have been revived, and many have been put on the fast track.

Water Resources Minister Nitin Gadkari recently tweeted that the government had decided to stop India’s share of waters in the Indus river system from flowing into Pakistan. Coming amidst noisy calls for a strong retaliation against the Pulwama terror attack, Gadkari’s statement seemed to indicate a new policy direction from the government. That clearly was not the case, as the government also clarified after some time. The policy direction had, in fact, changed more than two years earlier — in the wake of another terrorist attack, on an Army camp in Uri in September 2016.

After the Uri attack, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had said that “blood and water” could not flow together, and India had temporarily suspended regular meetings of the Indus Commissioners of the two countries.

A much bigger shift was signalled a few weeks later, when India decided to exert much greater control over the waters of the Indus basin, while continuing to adhere to the provisions of the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty that governs the sharing of these waters with Pakistan. A high-level task force was set up under the stewardship of the Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister to ensure that India makes full use of the waters it is entitled to under the Treaty.

Rights to be utilised

India has not been utilising its full claims, and letting much more water flow to Pakistan than has been committed under the Treaty.

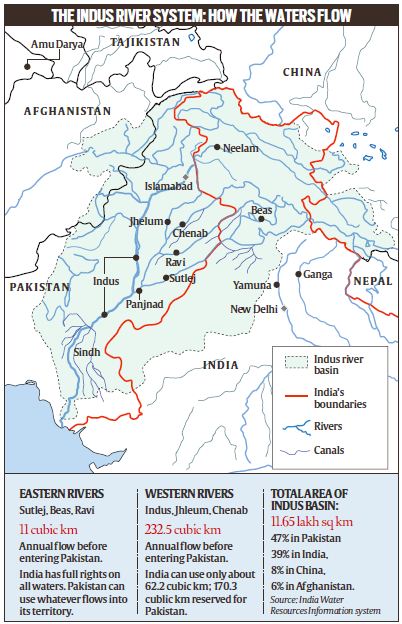

The Indus Waters Treaty gives India full control over the waters of the three Eastern rivers, Beas, Ravi and Sutlej — ‘Eastern’ because they flow east of the ‘Western’ rivers — while letting the waters of the three Western rivers of Indus, Jhelum and Chenab flow “unrestricted” to Pakistan. India is allowed to make some use of the waters of the Western rivers as well, including for purposes of navigation, power production and irrigation, but it must do so in accordance with the provisions of the Treaty.

Historically, India has never made full use of its rights, neither on the Eastern nor on the Western rivers. On the Western rivers specifically, there has been no pressing demand for creation of new infrastructure on the Indus rivers, either for hydroelectricity or irrigation. With a large proportion of farmers in Jammu and Kashmir having moved to horticulture from traditional crops, the demand for irrigation has gone down over the years. After the devastating floods of 2014, it was argued that storage infrastructure could have been built on these rivers as a flood-control measure.

As a result of India’s under-utilisation of its share of waters, Pakistan has over the years benefited more than it is entitled to under the Treaty. Pakistan’s dependence on the waters of the Indus basin cannot be overstated. More than 95% of Pakistan’s irrigation infrastructure is in the Indus basin — about 15 million hectares of land. It has now become the world’s largest contiguous irrigation system, comprising over 60,000 km of canals. Three of Pakistan’s biggest dams, including Mangla, which is one of the largest in the world, is built on the Jhelum river. These dams produce a substantial proportion of Pakistan’s electricity.

Post Uri, India’s decision to change the status quo and use more waters of the Indus rivers was made with the calculation that it would hurt the interests of Pakistan, which has become used to the excess water and built its infrastructure around it.

What moved after Uri

One that moved quickly was the 800MW Bursar hydroelectric project on the Marusudar river, one of the tributaries of the Chenab, in Kishtwar district of Jammu and Kashmir. Under direct monitoring of the Prime Minister’s Office, a revised detailed project report was finalised, prompt environmental clearance was granted, and an attractive rehabilitation package for affected families was disbursed. Recently, work has also been started. Bursar will be India’s first project on the Western rivers to have storage infrastructure.

The same happened with the Shahpur-Kandi project in Gurdaspur district of Punjab, work on which was stalled for several years because of a dispute between the governments of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir. In March 2017, the Centre summoned the representatives of the two states, brokered a solution, and directed that work be resumed.

A much bigger project, the 1,856-MW Sawalkot project on the Chenab in Jammu and Kashmir, was also given the final go-ahead in 2017, and work is expected to start soon. Similar is the case of the Ujh project in Jammu and Kashmir.

Officials say more than 30 projects are under various stages of implementation on the Western rivers, having got the final approvals. Many of these were started after the change in policy in 2016. Many of them have been accorded the status of national projects. Another eight projects are said to be in the planning stage.

Pakistan’s claims

Even before India’s shift in policy, Pakistan had often complained that it was being denied its due share of waters, and that India had violated the provisions of the Indus Waters Treaty in the manner it had designed and implemented many of its projects on the Indus rivers. In the last few years, several Pakistani academics have argued that the Treaty has failed to protect the interests of Pakistan, and that India has managed to manipulate the provisions in its favour.

The result has been an increasing number of objections being raised by Pakistan on the projects that are coming up in India. The two countries have permanent Indus Water Commissions that meet regularly not just to share information and data, but also to resolve disputes. Until a few years ago, most of these disputes would be resolved through this bilateral mechanism. The dispute over the Baglihar dam was the first one that Pakistan referred to the World Bank, which had brokered the Indus Waters Treaty.

Baglihar, which was adjudicated upon by a neutral expert, did not go Pakistan’s way. In the case of the Kishanganga project, where the matter was referred to a Court of Arbitration, a higher level of conflict resolution under the Treaty, Pakistan managed to get a partially favourable decision. Some disputes over the Kishanganga have remained unresolved and are currently being addressed.

In recent years, Pakistan has raised objections on many other projects, including the Ratle project, the Pakal Dul dam, and Sawalkot. Officials say the main objective of Pakistan seems to be to delay these projects, thereby forcing a cost escalation and making them economically unviable.

Last month, the Indus Commissioner of Pakistan was in India to visit some of these projects, as can be done once in five years in accordance with the provisions of the Treaty.