Snapshot

- An acceptance of our men who went to war for the Raj could perhaps offer a solution to the bitter ideological battles we face today.

The recognition that we as a people have a history of and a reputation for combat that is matched by few others in the world could ironically be the way forward to peace.

There is a famous anecdote that veteran soldiers tell about the Indian Army. During the days of the North African campaign during the Second World War, if you walked into the bar of the famous Shepheard’s hotel in Cairo, the barman always asked you which division you belonged to. If you answered Fourth Indian Division, you got a free drink on the house. The story might be apocryphal, but it illuminates a long forgotten bit of our own past – the glorious story of the Fourth Indian Division – widely regarded as one of the “greatest fighting formations in military history”.

The Prelude

The modern Indian Army as we know it owes its origin to the British Raj. It was not a force conceived to fight an all out overseas war but rather meant to be more of a policing force to keep the turbulent subjects of the Raj under check, while also keeping an eye out over the North West Frontier at Russian machinations. Even as late as the end of the First World War, Britain envisaged the North West Frontier with Afghanistan, and Bolshevist Russia beyond, as the major threat to India and hence the training and strategic planning of the Indian Army focused on deployment in this region rather than for any major global conflict. No one then could have foreseen another world war looming in the near future. But such are the ways of men and nations, that the crises of the future can seldom be foretold. When the World War Two broke out in 1939, the Indian Army found itself under-equipped, untrained and grossly unprepared to tackle the challenges posed by professional, highly trained and highly mechanised armies fielded by Germany and Italy.

Despite the well renowned courage and valour of the Indians, it was becoming apparent to British military planners that wars were no longer about just the human factor. The 1920s and 1930s had seen rapid advances in all spheres of industry and technology, and the Germans in particular were at the forefront of building the military-industrial complex. On the other hand, the lack of modernisation in the Indian Army was woeful. Britain had spent considerable expenses on modernising its own army to keep up with developments in Europe, acquiring tanks, anti aircraft guns and mechanising almost its entire cavalry from being horse mounted. By comparison, the Indian cavalry still remained horse mounted and its artillery guns were still mule drawn, and it possessed no anti-tank or anti-aircraft weapons. Such a force was to be pitted against state-of-art German Panzer tanks and Italian guns in North Africa.

Contrary to popular belief, the martial races theory was not what always determined recruitment to the British Army. The War was like a beast hungry for human blood and it devoured men like a forest fire devours dead grass. The British empire stretched to its limits in fighting wars on three fronts – Europe, North Africa and the Far East – needed men to feed its war machinery and these men came from India irrespective of their caste, region or religion. Against the highly mechanised forces of the Germans, men were like cannon fodder and the British could not afford to be choosy in whom they recruited. So, the martial races theory went for a toss as soon as the war began. Division sized Indian Army units had mixed composition from the various Indian regiments.

Thus while it is difficult to ascertain the exact regiment wise make up of the Fourth Indian Infantry Division, we know from various despatches and records that almost all the ethnicities of the Indian sub-continent were represented in it – Sikhs, Dogras, Rajputs, Pathans, Balochis, Marathas, Bengalis, Tamils, Garhwalis, Gurkhas – all fought shoulder to shoulder, distinguishing themselves in a far away land. Further, nearly a third of its strength was also provided by British troops. The fact that such a varied body of men so different in race, religion and language could fight as one, stood testimony to the time honoured traditions of the Indian Army and the superior soldierly qualities of the Indians.

The War In North Africa

As soon as the War broke out in Europe, the well prepared German Army drove through France like a hot knife through butter. By 1940 all French resistance had collapsed and the Germans now stood eyeball-to-eyeball against the British nation. A threatened Britain drew all her best forces for the defence of her homeland, leaving the defence of her vast and strung out empire to the Indian Army. With France under Axis occupation, Italy now focused its attention towards British possessions in North Africa.

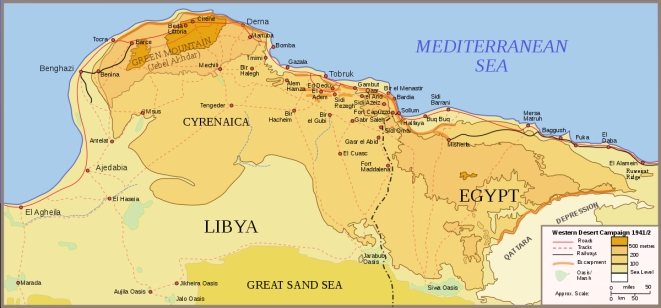

In the Western Desert, the British were in control of Egypt while the Italians ruled over Libya and Ethiopia. The North African Campaign began in August 1940 when Mussolini ordered the Italian forces based in Libya to invade Egypt. A further strategic objective of the Italian push into Egypt was to capture the Suez Canal – the crucial nerve centre of global shipping in those days. Whoever controlled the Suez controlled the lucrative shipping routes to the east, and since most of Britain’s empire lay to the east of the Suez, it could not afford to lose it. All that stood between Mussolini and the Suez Canal was a few British and Australian troops and the hastily assembled, poorly equipped Indian Army.

The Fourth Indian Infantry Division was the first formation to leave India for overseas service in Second World War, with the first tranche arriving in Egypt in August 1939. Its divisional insignia was a diving red eagle on a black patch, and its divisional motto was Jo Hukam – That Which Is Ordered Shall Be Accomplished – a motto which it was to live up to in all except its final and most tragic mission, where the famous Red Eagle was to fail miserably. But that comes later.

As the war raged on, the Fourth Indian Infantry Division came to be the most experienced division in the Middle East, with British Army commanders repeatedly falling back on the ‘Red Eagle’ for critical missions. The British forces in the region consisted primarily of the Western Desert Force under the Middle East Command led by General Archibald Wavell (later to be Viceroy of India). The Western Desert Force in turn was comprised of the Fourth Indian Infantry Division and the British Seventh Armoured Division – totaling 36,000 soldiers and 65 tanks in all. This force was to face the brunt of Mussolini’s 10th Army comprising of 1,50,000 infantry, 1600 guns, 600 tankettes (small tanks the size of a car used mostly by the Italian army) and 331 aircraft. At the outset, the odds seemed astronomical. The Indian and British soldiers were outnumbered almost five to one while lacking in artillery, armoured and air support as well. But it was precisely in fighting such incredible odds that the Fourth Indian Infantry Division earned its legendary reputation as one of the greatest fighting forces ever known in history.

The Desert Fox vs The Sepoy – The Defeat of Erwin Rommel

Nicknamed Operation Compass, the mission to drive the Italians out of North Africa lasted from December 1940 till February 1941. In February 1941, the division saw itself engaged in a bitter battle with the Italians in the town of Keren in Eritrea, located at the eastern edge of North Africa. Being their last foothold on the continent, the Italians fought furiously. It was here that Subedar Ricchpal Ram of the 4/6th Rajputana Rifles won the Victoria Cross, leading a gallant charge on the Italian positions despite being grievously wounded and having his foot blown off. So fierce was the battle of Keren, and such was the valour of Fourth Indian Division that once the battle was won, geographical features in East Africa were named after regiments of the Indian Army – Sikh Spur, Rajputana Ridge and so on.

By the time the Fourth Indian Division was done with its work in the Western Desert , it had stopped the Italian advance dead in its tracks, bringing the formidable 10th Army to its knees and forcing it to surrender. The exploits of the Fourth Indian Division led Anthony Eden, later to be the British PM, to exclaim, “never before has so much been surrendered by so many to so few”.

The following winter the Fourth Indian Division distinguished itself in Operation Crusader in which the German forces were led by none other than the famous Erwin Rommel – known as the Desert Fox – and his AfrikaKorps that was till then considered invincible. Rommel’s reputation as a commander was legendary and added to the technological and numerical superiority of the Axis forces, the result of the confrontation looked like a foregone conclusion. But once the Indians entered the battle, all strategic calculations of the enemy went for a toss. A British officer described the soldiers of the Fourth Indian Division fighting fearlessly against numerically superior German forces thus :

“After a while I saw the platoon advancing across the valley, turn west across a road, then in open formation return to attack another strongly held feature. I could not stop them…all we could do was provide supporting fire. What a sight! Twenty Five men attacking a high hill studded with enemy trenches…the enemy..300 or more of them..threw down their arms and surrendered to 25 men.”

Such intrepid heroism was to become the hallmark of the Fourth Indian Division as it stunned the enemy by its sheer fearlessness. Operation Crusader was the first victory, albeit a narrow one, by the British forces over the German ground forces in the Second World War, and more importantly the myth of invincibility of Rommel’s AfrikaKorps was forever shattered by the indomitable Indian sepoy. Rommel’s AfrikaKorps finally surrendered on 11 May 1943 to Lt Col C J Showers of the 1 Battalion, 2nd Gurkha Regiment, thus ending the war in North Africa for good. It’s work in North Africa completed the Red Eagle was then deployed to Syria. Later in 1944 they saw action in Italy where they fought at the famous battle of Monte Cassino along with the newly arrived American troops.

The Red Eagle saw its last major action of the Second World War when it was transferred to Greece which was then in the throes of a civil war. As the Germans withdrew from Greece, it became the battleground for the new war that was to engulf our world for the next 50 years – the Cold War. Soviet backed Leftist guerillas got embroiled in a bitter conflict with the American and British backed Greek government army. The Fourth Indian Division was involved in maintaining order during the bloody conflict which was in effect the first major conflict of the Cold War.

The Partition Of Punjab – The Fall From Grace Of The Red Eagle

By 1946 the Second World War was well and over but events in India had taken a precipitous turn. Imminent British withdrawal from India threatened to plunge the subcontinent into a whirlpool of violence. In particular Punjab, which had provided the bulk of recruits to the British war effort was now convulsed with a wave of violence as the newly returned soldiers who had not a few years ago fought shoulder to shoulder as brothers in arms now turned against each other in a frenzy of communal violence. The Fourth Indian Division was once again pressed into service, this time rechristened as the Punjab Boundary Force and tasked with stemming the communal violence in Punjab. However for the first time in its glorious history, the famous Red Eagle was to fail in its mission.

It’s by now legendary divisional motto of Jo Hukum – That Which is Ordered Shall be Accomplished – which it had lived up to throughout the deadliest conflict in human history was for the first, and the last time to fail. Where it had once fought insurmountable odds against the white man in Europe and in Africa, the Fourth Indian Division proved incapable of stemming the madness that had consumed its own people. The riots in Punjab, often led by disbanded army men who used tactics learned in the Army to organise genocidal violence, showed no sign of abating. As a result the Punjab Boundary Force was ignominiously disbanded soon after. With Partition, the Fourth Indian was divided, like many other British army divisions between India and Pakistan. Fifteen Battalions of the Fourth Indian Infantry Division were apportioned to India while 10 went to Pakistan where its remnants served with distinction.

Field Marshal Archibald Wavell, Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army and later Viceroy of India summed up the achievement of the Red Eagle:

“…. The Fourth Indian Division will surely go down as one of the greatest fighting formations in military history: to be spoken of with such as The Tenth Legion, The Light Division of the Peninsular War, Napoleon’s Old Guard….A mere summary of its record is impressive: in five years it fought nine campaigns, traveled more than 15,000 miles, suffered over 25,000 casualties, captured upwards of 150,000 prisoners…. Its campaigns include the great victory of Sidi Barrani,…a gallant costly assault at Cassino against defences even more formidable than at Keren…the successful breaching of the Gothic Line….The Fourth Division has a claim on history even beyond its fighting capabilities…. and its commanders will always salute one of the greatest bands of fighting men who have ever served together in this troubled world of wars and warriors.” (Das:380)

The British Indian Army – A Conflicted Legacy Of Heroism And Valour

As a nation we are yet to come to terms with our men who went to war for the British. Nationalism all over the Third World were shaped to a large extent by their opposition to colonial ‘other’. The presence in this narrative of a large body of men who went to war for the supposed oppressor acts like a non-sequitur, disrupting the neatly drawn contours of the nationalist narrative. What does one make of these men who fought heroically in places far and wide, who carried proudly the name of the Indian nation where it was never known, but drew their pay from the hated colonial master? For the Indian national movement this posed a tricky question.

In the years immediately following Independence, this question was dealt with by shoving it under the carpet. In the utopian Nehruvian worldview, there were to be no more wars and hence the inconvenient question of accommodating the mercenary-warriors of yore was best left unattended. All of a sudden the millions of Indian soldiers who fought heroically in the two World Wars found themselves on the wrong side of history, their stories destined to be forgotten for forever. It took almost half a century, four full blown wars with our new neighbours, and efforts by academic movements such as the Subaltern Studies group and various oral history projects to once again bring to the centre the question of soldiers of the British Indian Army and their place in the national imagination. The debate is now slowly moving from the academic to the popular realm, as shown by the outcry over Dunkirk, and the sudden flux of historical works relating to the Indian contribution to the two World Wars.

The presence of Bose as a towering figure in Indian nationalistic pantheon further complicates the picture. Bose was a man who raised his own ‘Indian’ Army and joined hands with the Nazis against the British. The Indian National Army was promptly accommodated in the national narrative and accorded the status of heroes. However, the placement of a national hero on the same plane as a genocidal dictator sat uneasily, while leaving the question of the British Indian Army still unanswered. These unresolved conflicts deeply polarised the Indian psyche paving the way for ideological conflicts of the future.

These mercenaries of the Raj also complicate the Gandhian conception of Indians as a peace loving nation that was to form the bedrock of the Gandhi-Nehruvian ‘idea of India’. This was a conception that outraged the Hindu far right and perhaps led to the birth of a militant Hindu nationalism whose entire raison d’etre seemed to be to disprove the Gandhian pacifist conception of Indian history. Both the Gandhian notion and its reactionary far-right counter, in fact, arose because each completely chose to ignore the reality.

Perhaps, because, each was born out of elite politics removed from the ground realities, neither cared to factor in the ubiquitous peasant-soldier in its ideological calculations. That the British were able to raise the largest volunteer army ever raised in the history of mankind from India speaks volumes about the martial culture of the land. Soldiering has throughout Indian history been viewed as a right and honourable profession. The British soon realised that such a cultural predisposition to war, violence, and soldiering made Indians among the finest soldiers on earth, and used the knowledge to build their empire on the shoulders of the humble sepoy.

The Mahatma on the other hand, for all his love for the masses, failed to account for the millions of Indians who relied on violence for a living, and excelled at it. Professional soldiers and trained killers, these were men, who took their pay from the British, did what they were told to, and were proud of it. As the historian Raghu Karnad puts it – “the Indian army was a body of professional soldiers trained to uphold the illegal occupation of not just their own land but of others as well”.

The image of the disciplined professional soldier fighting in the deserts, jungles, trenches, and quietly accepting death over dishonor contrasted sharply with the kurta and corduroy clad men sitting in ornate chambers and plotting their sinister schemes to divide a nation in their lust for power. Today, we would know exactly which side we would root for in such a picture. In the turbulent 30s and 40s though, such an image only served to confound the neat narratives that all stakeholders in the political game were trying to construct. Since no one could make any sense of him, nor assign to him an easily recognisable label of hero or anti-hero, the soldier who went to war was thus relegated to a vacuum of the national imagination where he has been forced to remain till this day.

An acceptance of our men who went to war for the Raj could perhaps offer a solution to the bitter ideological battles we face today. We need to reconcile ourselves to the complex web of loyalties that define the nature of human interactions, and which are impossible to bracket into simple nationalistic binaries. Inherent to such reconciliation is the idea that the sepoy could draw his pay from the white man and yet have his heart beat for an independent Indian nation. The recognition that we as a people have a history of and a reputation for combat that is matched by few others in the world could ironically be the way forward to peace. These were our men, and these are our histories. It is time we own up to them.